Revd Thomas Conant (1785-1870)

The 19th century Baptist preacher Thomas Conant was proud to be a descendant of East Budleigh-born Roger Conant. Naturally enough he took pride in his famous ancestor’s role as a pioneer of Massachusetts, seen as the founder of the city of Salem. He was also proud in his erroneous belief that he was descended from Huguenot stock. Perhaps he identified with French Protestants because he, like them, had suffered for his Baptist faith.

A famous 19th century cartoon 'The American River Ganges' by

Thomas Nast depicting Roman Catholic bishops as crocodiles attacking America’s public

schools, with the connivance of Irish Catholic politicians. Published in the 8

May 1875 edition of Harper's Weekly. Image credit: Wikipedia

Perhaps also, in common with the Protestant majority in 19th century America, he shared a mistrust of Catholics. It seems that religious thinking in Thomas Conant's time still had echoes of the 16th century European Reformation which had inspired so many Puritans to settle in North America.

Some 19th century American leaders and preachers still saw the Catholic Church as the Whore of Babylon, mentioned in the Bible. They were alarmed by the influx of Irish Catholic immigrants, blaming them for spreading violence and drunkenness and destroying the culture of the United States.

Photograph of Lyman Beecher (1775-1863)

Preacher and moral crusader Lyman Beecher, born in Connecticut in 1775, was much influenced by the thinking of Jean Calvin, the 16th century theologian who had inspired so many Huguenots. In ‘A Plea for the West’, published in 1835, Beecher railed against ‘foreign emigrants whose accumulating tide is rolling in upon us’. They were, he affirmed, controlled by a ‘priesthood educated under the despotic governments of Catholic Europe’. They resembled, in his words, ‘an army of soldiers, enlisted and officered, and spreading over the land’. Americans should have ‘just occasion to apprehend danger to our liberties’.

In heady, apocalyptic language he claimed: ‘Clouds like the locusts of Egypt are rising from the hills and plains of Europe, and on the wings of every wind are coming over to settle down upon our fair fields; while millions, moved by the noise of their rising and cheered by the news of their safe arrival and green pastures, are preparing for flight in an endless succession’. He believed that Catholics were establishing schools in the United States as part of a foreign plot to convert Protestant students.

‘Ruins of the Ursuline Convent, at Charlestown, Massachusetts,’ historical print, 1834, collection of the Charlestown Historical Society. Image credit: Wikipedia

Not surprisingly, Catholics complained that Beecher was responsible for encouraging arsonists to burn the Ursuline Sisters’ convent near Boston, following the sermon which he gave in the city in the year before ‘A Plea for the West’ was published.

All Saints’ Church, East Budleigh. Image credit: Peter Bowler

Thomas Conant may have been wrong in ascribing a French

element to his ancestry, but there was an indirect Huguenot connection to Roger

Conant, back in Devon, England. It was through the church of All Saints in East

Budleigh where Roger’s father Richard, like Sir Walter Ralegh’s, had been church warden.

I’m sure that had he known about it, this link would have thrilled Thomas

Conant, suffering as he did for his non-conformist religious beliefs.

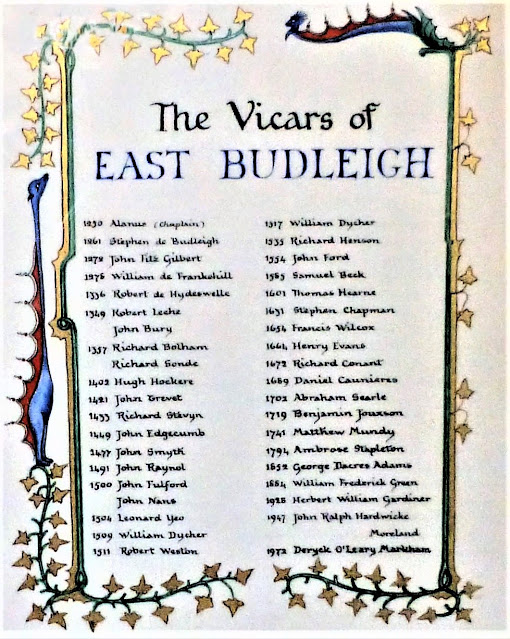

While on holiday in the Budleigh area about 30 years ago I visited All Saints’ Church. The list seen in the above photo replaced an older plainer version, and on that original list I was astonished to see immediately after Richard Conant’s name: ‘1689 Daniel Caunieres, French’.

I wonder why the church omitted that mention of this obviously Huguenot refugee’s nationality in the newer, decorated version. At one stroke they had removed one of the most interesting facets of the history of All Saints’ Church.

There are plenty of other fascinating things to see in All Saints’ Church,

including the celebrated carved oak bench ends dated 1537. This one depicts....

what? A mythical green man, as most historians believe? Or a Native American in

the view of many residents of the village?

View of the Chapel at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in Cantabrigia Illustrata by David Loggan, published in 1690. Image credit: Wikipedia

The previous vicar, Richard Conant, was a nephew of Roger himself. Born in 1622 to Roger's brother Richard (1581-1625) and his wife Jane, née Slade, he graduated from Emmanuel College Cambridge in 1645. Sir Walter Mildmay, once a Chancellor of the Exchequer under Queen Elizabeth I, had founded Emmanuel College in 1584 to educate Protestant preachers. By the 1620s it was the largest college in Cambridge and had a reputation as a hotbed of Puritanism.

The memorial to William and Richard Venn in St Michael’s Church, Otterton. It records how Richard Venn, born at Otterton in 1601 and instituted as vicar, was ‘ejected from his living in 1645 for his loyalty to his Church and King’. Image credit: www.findagrave.com

Richard Conant evidently had Puritan sympathies which favoured him during the time of the English Civil War and Oliver Cromwell, for in 1645 he was appointed a minister of St Michael’s Church in the nearby village of Otterton. His predecessor, the royalist Revd Richard Venn, was ousted.

Portrait of King Charles II, crowned at

Westminster Abbey on 23 April 1661, by the English portrait painter John

Michael Wright (1617-94). Image credit: Wikipedia

At the restoration of Charles II in 1660, things changed again. Royalists were back in favour, and it was the turn of the Puritan Richard Conant to be ousted. He is recorded as continuing ‘to live privately in the Parish & was a Nonconformist at St Bartholomew's day & a good while after, but at last he conformed & was presented to East Budleigh’.

Richard Conant was vicar of All Saints’ Church from 1672 until his death on 6 December 1688, being described, according to Budleigh Salterton antiquary Dr Brushfield, as ‘a hardworking, painstaking, exemplary clergyman’.

Looking

down on All Saints’ graveyard from the church tower. There are plenty of other

interesting graves at All Saints, including

memorials to Admiral Preedy, captain of one of the two ships which laid the first

successful transatlantic telegraph cable in the 19th century

He was buried at

All Saints. I

can find no evidence of his grave in the churchyard, but it was a long time

ago. However it’s the life of Richard Conant’s successor, the Huguenot Daniel Caunieres,

which fascinates me. His grave can be seen, but not in East Budleigh.

It seems likely that his family originated from Western France, home for many Huguenots Finding him as vicar of East Budleigh church suggests that on his arrival in England he may well have been part of one of the largest Huguenot communities in Devon, at Exeter.

Daniel may indeed have been a Huguenot minister in France, and if so, like many others who came to England as refugees, would have found himself faced with a dilemma: should he remain faithful to the form of worship that he had known in France, or accept the Anglican ways?

St Olave’s Church, Fore Street, Exeter

Huguenots who

accepted the Anglican form of worship including the Church of England Prayer

Book, while retaining the use of French, were known as conformists. In Exeter

they were rewarded when the ancient St Olave’s Church on Fore Street was made

over to them following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. They continued to

use it until 1758. One of them, Jacques

Sanxay became pastor at St Olave’s in 1686 until his death in 1693. The non-conformist Exeter congregation existed

from 1686 until 1729, but it is not known where it met.

Raymond Gaches Image credit: www.huguenotmuseum.org

As for conformist Huguenot ministers who actually held office as vicars in Anglican churches, Daniel’s case would not have been unique. A well known example in the Church of England was Raymond Gaches, the son of a judge, born at Castres in the Languedoc region of France around 1615. Moving to England, where he died in 1681, well before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, he eventually became vicar of Barking in Essex.

Even so, mastery of the English language as well as assimilation of Anglican practices cannot have been easy for such refugees. But on 24 May 1689 Daniel Caunieres was named vicar of East Budleigh. Perhaps he had the support of influential friends in the diocese of Exeter, in which East Budleigh lies.

A statue of William III, who landed at the Devon coastal town of Brixham on 5 November 1688. In a bloodless revolution he took the throne from James II who went into exile. Image credit: Steve Daniels - Wikipedia

Bishop Jonathan Trelawny had moved from Bristol by this time, having been summoned to London by James II and given the bishopric of Exeter following the landing of the Protestant William of Orange at Brixham, Devon, on 5 November 1688. It was a strange appointment in view of the bishop's opposition to the Declaration of Indulgence proclaimed by the king. Trelawny had been one of the 'Seven Bishops' who had been charged with seditious libel before being acquitted by a jury on 30 June of that year. But the appointment seems to have been a last-ditch vain attempt by James to seek support.

With the 1688 Glorious Revolution and Catholic King James’ deposition and flight to France in December that year it was back to a Protestant monarchy for Britain. On 13 February 1689, Trelawny had formally voted for the proclamation of William and Mary as joint king and queen to replace James II. He was installed as Bishop of Exeter two months later on 13 April, remaining there until 1707.

The vicarage, known as ‘Vicar’s Mead’ on Hayes Lane, East

Budleigh. This ancient building was where young Walter Ralegh was first taught,

and where Daniel Caunieres lived

Certainly Daniel was confident enough to call on the support of

Bishop Trelawny when in the following year, 1690, he complained about his

accommodation. Along with his Patron, Richard Duke, and the church wardens, he

reported to Bishop Trelawny that the Vicarage House was in a ruinous condition, ‘the

greatest part of it standing vpon Posts, and some of it fallen down.’ It was

also, he complained, ‘too large for so Poor a Place,’ and requested permission

for it to be ‘reduced to a less spacious and more convenient Habitation’. The

Bishop agreed, and allowed money to carry out the alterations.

Daniel was Vicar of East Budleigh for about twelve years, and during this period the Registers record the baptism of nine of his children, and the burial of two. An entry for 4 July 1694 records the baptism of ‘John son of Mr Daniel Canniers’ and in the following year on 30 August we find ‘Samuel son of Daniel Caunieres vic’, the last word obviously standing for ‘vicar’. On 22 September 1696 we find the baptism of ‘Abraham son of Dan Caunieres’, and for an unreadable date in October 1697 ‘Samuel son of Dan Caunieres’. This would sadly suggest that the earlier Samuel, born on 30 August 1695, had died in infancy. On yet another unreadable date in March 1698 we find the baptism record for ‘Hannah dau of Dan Caunieres’.

A few months later, the burial records of East Budleigh tell us that Daniel and his wife lost their little two-year-old son Abraham, buried on 8 May 1698. Did they lose another son, for there is a burial record for ‘Henry Conyers?Couzens’ dated 2 July 1699? Perhaps not, for there is no record of the birth of Henry Caunieres. In the following year, Daniel and his wife seem to have been blessed with twins, as the baptism entry for 14 March 1700 is for ‘Isaac and Jacob sons of Dan Caunieres’.

St Michael’s Church East Buckland

The new century saw

the Caunieres family move from East Budleigh to North Devon. Here he would benefit

from even more powerful patronage than the diocesan support that he had enjoyed

in his first ministry. On 15 June 1702 he was appointed as Rector of the parish

of East Buckland, which had been left vacant by the death of the previous

incumbent the Revd John Polewheel. The actual date of Daniel’s move from All

Saints’ Church is unknown, but by 31 October of that year his successor at East

Budleigh was named as the Revd Abraham Searle.

East Buckland was and is a tiny hamlet but importantly it was part of the large estates owned for centuries by the Fortescue family, whose roots can be traced back to the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Effigies of Hugh Fortescue (1544-1600) and his wife Elizabeth née Chichester (1545-1630)

Kneeling effigies of John Fortescue (1571-1605)

of Filleigh and of Weare Gifford Hall, Devon, and of his wife Mary Speccot (1575-1637)

Various features in local churches testify to the importance of the Fortescue family, like this 1638 mural monument in Weare Giffard Church, erected to honour three generations of the family. When Daniel became Rector of East Buckland the local landowner was Hugh Fortescue, notable for his absences as a Member of Parliament but successful in finding a well endowed wife when in 1692 he married Barbara Boscawen. She was the only daughter of Hugh Boscawen, another MP. Hugh Fortescue’s enormous wealth increased even more when he succeeded to his own family estates the following year.

The East Buckland

part of the estates consisted mainly of farmland, but included a copper mine described

in the 18th century as still being a source of good quality ore.

The Fortescue

family had combined consolidating its riches with Puritan sympathies in

religious matters. Hugh Fortescue’s grandfather, also named Hugh, had married into

another family notable for its support of Parliament during the English Civil War

when he married Mary, daughter of Robert Rolle. The whole Rolle clan was

seen as deeply and traditionally Puritan, having a hatred of practices such as

usury and gaming.

St Pauls’ Church Filleigh, built in 1732 to replace the old medieval church and designed, it has been said, to be 'a Gothic eyecatcher' Image credit: Wikipedia

Daniel stayed only two years at East Buckland before resigning

in favour of another appointment in a neighbouring village. On 19 January 1704

he was admitted as Rector of Filleigh, a position which had been vacant following

the death of its minister the Revd William Arundell. At East Buckland, on 17

July that year, Daniel’s successor was named as the Revd Thomas Chapman.

A church brass showing Richard Fortescue (c.1517-1570). It was one of the memorials taken from the old medieval church. Image credit: Wikipedia

As in East Buckland the Fortescue family was prominent. In Filleigh

Church you can see the bearded figure of Richard Fortescue, who died during the

reign of Elizabeth I. ‘Here lyeth Richard Ffortescue of Ffylleygh,

Esquier, who dyed on the last daye of June in the yere of oure lorde god 1570’ reads

the inscription. In the new parish, Hugh

Fortescue continued to be Daniel’s patron as the most important landowner in

the area, but he died in 1719.

Hugh Fortescue, Earl Clinton. From the Collection of the Countess of Arran

His 23-year-old son – yet another Hugh! – inherited his estates.

But he also inherited an ancient English barony through a family link which by

coincidence leads to Salem, the American city founded by Roger Conant!

The Great

Tower of Tattershall Castle showing the three separate entrances. Image credit:

Wikipedia

The title of Baron Clinton had been held for centuries by the Earls of Lincoln, whose family seat of Tattershall Castle lay on the other side of England, on the east coast. The young Hugh Fortescue’s mother, Bridget Boscawen, was descended on her mother’s side from a family noted for its Puritan sympathies even more than the Rolle family.

Religion would have been a popular subject of conversation with the family at Tattershall Castle, especially as the area was a hotbed of separatist Puritans who wanted a complete break from the Church of England. Many of the Plymouth Pilgrims who set out for the New World on the Mayflower in 1620 came from Lincolnshire.

Bridget’s maternal grandfather Theophilus Clinton, became the 4th Earl of Lincoln in 1619 and soon became involved on the side of Parliament in the conflict with Charles I which would lead to the Civil War. In 1626, as the author of a pamphlet in which he opposed King Charles I’s forced loan and accused the King of seeking ‘the overthrow of parliament and the freedom that we now enjoy’, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Three of Theophilus’ six sisters would marry men involved with Puritan-backed expeditions to the New World in the 17th century. Lady Susan Clinton and her husband Sergeant-Major-General John Humphrey emigrated in 1634 to Massachusetts, where he served as a magistrate, but the couple returned to England in 1641. Her younger sister Lady Frances Clinton, married John Gorges, Lord Proprietor of the Province of Maine, a title that he inherited from his father Sir Ferdinando Gorges.

Their eldest sister Arbella would become the wife of a Puritan clergyman and achieve iconic status in the story of the American nation, following her death at Salem in 1630. The Salem-born author Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about her in his story 'Grandfather's Chair'. It’s been said that ‘American history, according to Hawthorne, begins with the story of Lady Arbella Johnson’.

The Arbella, Governor Winthrop’s Flagship, on

which Arbella Johnson and her husband sailed to America. The ship was originally

called The Eagle but was renamed in honour of Lady Arbella. Image credit: Wikipedia

However that is another saga. For the time being, I just hope to intrigue you with this image showing a replica of the ship Arbella which was built for the 300th anniversary of Salem in 1930 in conjunction with the city’s Pioneer Village, the first living history museum in the United States, which opened in June that year.

But back to Huguenot minister Daniel Caunieres, who by now is a respected clergyman of the Church of England, yet with a religious background which may have struck a chord among members of the Clinton and Rolle families, known for their Puritan sympathies.

On 10 March 1722 Daniel

was appointed as chaplain to the young Hugh Fortescue, now titled as 1st

Earl and 14th Baron Clinton, of Castle Hill in the parish of

Filleigh and of nearby Weare Giffard Hall. Although still a rural clergyman Daniel’s

position must have felt secure and comfortable, for his patron was clearly becoming

more influential by the day. On 16 March 1721 Fortescue was summoned to the

House of Lords in London as Baron Clinton, and in the same year was appointed by King

George I as Lord Lieutenant of Devon. In 1723 he was appointed a Gentleman of

the Bedchamber to the Prince of Wales, the future King George II. In 1725 he was

made a Knight of the Bath, also by King George I.

There was also a rise in status for Daniel Caunieres. On the death of East Buckland’s Rector Thomas Chapman

in 1723, the two benefices of Filleigh and East Buckland were united by a legal

instrument dated 30 December of that year. Daniel, who had continued to retain the

incumbency of Filleigh, was appointed to the joint rectorship.

The two combined benefices still amounted to no more

than a small parish. In 1744, a report known as an Episcopal Visitation Return counted

about 24 families in total, giving a figure of about 70 communicants, of whom about

20 usually received. All of course, were content to abide by the traditions of the

Church of England. ‘There is no dissenter of any kind’ noted the Episcopal Visitation

Return.

Meanwhile Hugh Fortescue, in keeping with his grand titles, set about making his mark on the North Devon landscape. He was already wealthy. From his mother Bridget Boscawen the Fortescue family inherited various estates in Cornwall including mines at Treore, and also possessed Trewether and the harbours in the Cornish towns of Port Gaverne and Port Isaac.

He now consolidated his estates by selling most of his holdings in Somerset and Wiltshire and reinvesting the proceeds of £22,000 in purchasing more land in the vicinity of Filleigh. The ancient manor house inherited from his father was demolished, and Lord Burlington, Britain’s pioneer and arbiter of the style of architecture associated with the 16th century Venetian architect Andrea Palladio, and known as Palladianism, was consulted on the design of Fortescue’s proposed new mansion. In 1728 Hugh Fortescue appointed Burlington's favoured builder Roger Morris to reface the house in Portland stone.

Engraving of Castle Hill in 1830. Drawn by T.

Allom, engraved by T. Dixon. Image

credit: Wikipedia

The new mansion, completed in 1730, has been

described as ‘a rare example in the county of an 18th century

country mansion on the grand scale’, and presumably Daniel would have been a

regular visitor, marvelling at its magnificence.

Also demolished

along with Filleigh’s manor house was the old medieval church, which did not

fit in well with the design for Hugh Fortescue’s Palladian mansion. A new church was built in 1732 on a site half

a mile west of Castle Hill, designed to be visible from the mansion’s terrace. One

imagines that Daniel would have been involved in discussions about such building

projects.

Castle

Hill in 2014. The architectural ‘sham castle’, built in 1746, is on the hill

behind. Image credit: Wikipedia

Image credit:

Daniel died on 10 February 1739. The Burial Register of Filleigh contains

this entry: ‘1739.

Daniel Conyers, Late Rector of this Parish was buried Feb 12th according to Law

in Woollen only as was testified upon oath by Jane Gardener before E. Bartlett

Rector of West Buckland.’

Could

there be somewhere in Castle Hill a painting showing Daniel as a respected

friend and spiritual advisor to the Fortescue family? Certainly he seems to have been highly

regarded by his parishioners. He

was interred in Filleigh Churchyard, and his gravestone bears this inscription:

‘Here lyeth the body of Daniel Caunieres late Minister of this Parish whose extraordinary Piety & eminent Vertues will render his memory for ever valuable to all posterity’. He died Feb. 10th 1739 aged 78.’

Are his descendants still in Devon? I wonder whether they are aware of him. We know that Daniel’s son Ely joined the Navy, for the latter’s Will records him as ‘belonging to His Majesty’s Ship Weymouth’.

There are no doubt other individuals who are descended, but with slightly different names. In his monumental work in honour of Roger Conant, the genealogist Frederick Odell Conant mentions Connet, Connett and Connit families. The Caunieres name is likely to have undergone similar changes. As the excellent Budleigh Salterton historian Dr Brushfield noted: ‘The manner of spelling his name exhibits considerable variation. In the Register of East Budleigh it is written Cauniers, and in that of Filleigh, Conyers. It is Conyer in a document in the Bishop's Registry, and Dr. Oliver has Conniers. There is no doubt as to Caunieres being correct, as it appears so in the parish books in his own writing.’

So, if you’re planning to visit East Budleigh, perhaps hoping to find traces of Roger Conant, do remember that this charming village has much more to offer: Ralegh of course; the stained glass commemorating Admiral Preedy, whom I’ve already mentioned. But at a time of refugees still fleeing persecution in their homeland I like to remember how much the Huguenots contributed to the countries which took them in nearly four centuries ago, and how Frenchman Daniel Caunieres found shelter and a new life in a welcoming Devon.

The story of why a French Huguenot like Daniel Caunieres may have been appointed as vicar of East Budleigh is at https://conant400.blogspot.com/2022/02/48-divines-and-dissent-in-roger-conants.html