From the top: All Saints' Church, where Daniel Caunieres (1661-1739) was vicar; East Budleigh High Street; Salem Chapel, on Vicarage Road

It’s a typically English picture postcard village, its thatched cottages neatly lining the High Street as it stretches down from the ancient church. So that second place of worship on the outskirts of East Budleigh has often struck me as incongruous, like a piece of ill-fitting jigsaw puzzle.

As incongruous as the fact that back in the 17th century the typically English ancient church had Frenchman Daniel Caunieres as its vicar. Maybe the two incongruities are connected.

A painting of the St

Bartholomew’s Day massacre by François Dubois, a Huguenot painter (1529-1584) born in Amiens, who settled in Switzerland. Although Dubois did not witness the

massacre, he depicts Admiral Coligny's body hanging out of a window at the rear

to the right. To the left rear, Catherine de' Medici is shown emerging from the

Louvre Palace to inspect a heap of bodies. Image credit: Wikipedia

Could one answer lie somewhere in the extraordinary life of East Budleigh’s most famous historical figure? We know that young Walter Ralegh left the village, aged possibly as young as 14, to go across the Channel and fight in France on the side of fellow-Protestants during those savage Wars of Religion.

He seems to have been present when Catholic and Huguenot forces met at the Battle of Moncontour near Poitiers on 3 October 1569, and may even have witnessed the horrors of the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572.

Could he have met the Caunieres family? Maybe he

told them: ‘Look me up in East Devon if you’re ever forced to leave your

homeland by those horrid Papists’. And just over a century later, when French

king Louis XIV stupidly revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, someone in Daniel’s

family remembered Walter’s longstanding invitation. Protestant England would

welcome persecuted ‘godly’ Huguenots. Wouldn’t Devon be a perfect refuge for them

when life in France had become so intolerable?

Ralegh (c.1552-1618) and his History of the World, first published in 1614. This portrait in All Saints’ Church, East Budleigh is a copy of one of the best known portraits of Sir Walter formerly attributed to Zuccaro but now to the monogrammist 'H' (? Hubbard) and dated 1588. It shows Raleigh in court dress at the height of his favour with Queen Elizabeth I

A fanciful idea of course. It’s true that Ralegh in his History of the World seems to refer to episodes in the French Wars which he may have witnessed, but nowhere does he mention French friends that he may have made at that time.

Two of a set of playing cards on the theme of the Popish Plot, depicting i. Oates revealing the Plot to King Charles II; ii. The execution of the five Jesuits, falsely accused of conspiring to kill the king and replace him with his Catholic brother the Duke of York (later crowned as King James II). Image credit: Wikipedia

But what if the diocesan authorities in Exeter in

1689 had an ulterior motive in appointing the Huguenot Daniel Caunieres as

vicar of East Budleigh?

It has been said that no evidence of organised dissent in East Budleigh has been traced before the end of the 17th century. However the noticeable Puritan background of its vicars from the time of the Civil War may indicate that there was a sizeable part of the congregation which would ultimately separate itself from All Saints’ Church. Typical of Presbyterians, they would reject the hierarchy of the Anglican establishment with its bishops and become members of the nonconformist Salem Chapel.

Daniel Caunieres was appointed vicar during a

century when Catholics had been blamed for the Gunpowder Plot and the Great

Fire of London. Three years of anti-Catholic hysteria had been whipped

up between 1678 and 1681 by the pathological liar Titus Oates with his tales of

a Popish Plot.

For church congregations, especially in Devon with

memories of Drake and the Spanish Armada, the threat of a Papal-backed invasion

was longstanding. Spain and France, the leading Catholic powers in Europe, were

still seen as England’s natural enemies. By 1689 East Budleigh would presumably

welcome a vicar whose Protestantism and ‘godliness’ was beyond doubt and who

had suffered for his faith in his native France.

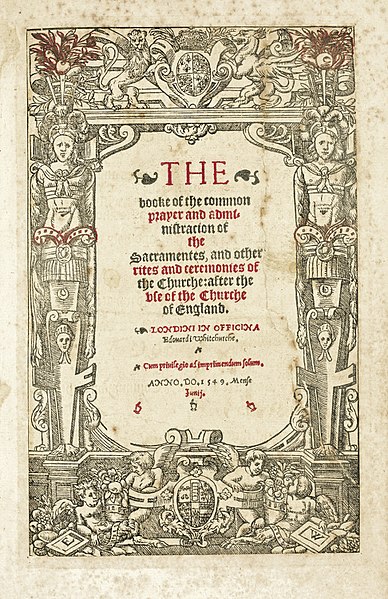

The title page of the 1549 edition of the

Book of Common Prayer, a publication which initially got a hostile reception in some parts of England, including in East Devon

How ‘godly’ was East Budleigh I wonder? We know that in the early days of the Reformation

its churchwarden Walter Ralegh Sr, father of Sir Walter, had embraced the English

government’s religious policy under the Protestant King Edward VI.

Portrait of John Hooker (c.1527–1601) of

Exeter. British (English) School, 16th/17th century. Royal Albert Memorial

Museum, Exeter. Image credit: Wikipedia

John Hooker, the 16th century Exeter-born historian and twice Member of Parliament for the city, relates an episode involving Ralegh during the Prayer Book

Rebellion of 1549, when people in Devon and Cornwall loyal to traditional Catholic rituals in their

churches revolted against the imposition of the Book of Common Prayer in

English parishes.

Angry villagers from Clyst St Mary, a few miles south-east of Exeter, were stirred into action, ‘like a sort of Wasps’ as Hooker’s history puts it, digging trenches and building fortifications to defend themselves against government forces.

During the consequent battle on 5 August 1549, thousands of ill-armed rebels were slaughtered, including 900 bound and gagged prisoners.

Replica of a Tudor rosary found on board the 16th century carrack Mary Rose. A similar replica is on display in the Ralegh Room at Fairlynch Museum in Budleigh Salterton. Image credit: Peter Crossman - Wikimedia

According to Hooker’s account, the trouble at Clyst

St Mary had started when Ralegh, while riding from East Budleigh to Exeter, chanced to meet and rebuke an old woman of the village for her illegal use of

rosary beads, the Catholic practice of reciting prayers using such beads having

been banned in England in 1547.

Walter Ralegh Sr was shown in Hooker’s

chronicle as a confirmed Protestant, insisting, as he told the old woman of

Clyst St Mary, that Religion ‘was for the future to be that of the Reformed, as

by Law established’. His wife also appeared in a contemporary account which

leaves us in no doubt as to her religious sympathies.

One of the gory images from the 1563 edition of John Foxe's Book of Martyrs: Hugh Latimer (c.1487-1555) and Nicholas Ridley (c.1500-1555) martyred by being burnt at the stake. Image credit: Wikipedia

The 1583 edition of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs included an account of the trial and execution of the Cornish woman Agnes Prest, charged with heresy in 1557 and imprisoned in Exeter during the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary. Foxe’s book tells us how Katherine Ralegh, ‘a woman of noble wit, and of a good and godly opinion’, visited Agnes and how impressed she was by the prisoner’s demeanour and knowledge of Scripture.

An episode in the life of Agnes Prest (1503-1557) from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. She is rebuking a stonemason for his work repairing statues, telling him, 'What a madman art thou, to make them new noses, which within a few days shall all lose their heads!' Illustration by the German-born artist Joseph Martin Kronheim (1810–1896) from the 1887 edition of the Book of Martyrs. Image credit: Wikipedia

In his account, Foxe makes a point which would appeal to many of his readers: understanding the word of God is not exclusive to a learned elite, but rather is accessible to all.

On Katherine’s return, ‘as soon as she

came home to her husband, she declared to him, that in her life she never heard

a woman (of such simplicity to see to) talk so godly, so perfectly, so

sincerely, and so earnestly; insomuch, that if God were not with her, she could

not speak such things, “to the which I am not able to answer her,” said she, “who

can read, and she cannot.”’

Bronze relief sculpted panel by Harry Hems (1842-1916) on the Protestant Martyrs’ monument in Denmark Road, Exeter, erected in 1909. It depicts the burning at the stake of Agnes Prest in 1557. Image credit: Wikipedia

One presumes that Katherine Ralegh would have related the story of the Protestant martyr Agnes Prest not only to her husband but also to her network of friends and relatives in East Devon and further afield. The mother of the future explorer and Queen Elizabeth’s favourite courtier, was indeed a ‘worthy gentlewoman’ from a well connected Devon family. Born Katherine Champernowne, she was also the mother of the adventurer Sir Humphrey Gilbert and was closely related to Katherine Ashley (née Champernowne), governess and Lady of the Bedchamber as well as close friend to Queen Elizabeth I.

The Book of Martyrs was widely owned and read by

English Puritans and, it is said, helped to form British opinion on the

Catholic Church for several centuries.

Whether

or not Foxe was historically accurate in giving the details of Katherine Ralegh’s

conversation with Agnes Prest, his book reinforced

people’s hatred of the Papacy by portraying it, along with the Spanish

Inquisition and Catholic monarchs like Queen Mary, as agents of the Antichrist.

The

Rolle Arms, one of East Budleigh’s two pubs. In Budleigh Salterton, one of the

town’s best hotels was The Rolle Arms on the High Street, since demolished and

converted to flats as The Rolle

Puritan

preachers who drew on such anti-Catholic themes in their sermons found support

in all classes of Elizabethan and Stuart society, including from powerful

patrons in the aristocracy.

Many influential landowners such as members of the

Rolle family – a well known name in our corner of East Devon – backed Parliament

rather than the King during the English Civil Wars.

A biographer of Robert Rolle, the 17th century Member of Parliament, has written that the whole Rolle clan was seen as deeply and traditionally

Puritan, having a hatred of practices such as usury, gaming at cards and dice.

Top: The view looking towards the village of Clyst St Mary, outside Exeter, across the medieval bridge and causeway across the River Clyst. This was the scene of a bloody encounter between Catholic rebels and Protestant forces loyal to King Edward VI (1537-1553) during the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549. Image credit: Derek Harper. The lower image shows the Battle of Sedgemoor memorial stone, marking where the Duke of Monmouth (1649-1685) was defeated by royalist forces in 1685. Image credit: Ken Grainger

The story of how East Devon moved from its

traditional support of Catholicism at the time of the 1549 Prayer Book

Rebellion to the Protestantism which motivated West Country people in the

Monmouth Rebellion of 1685 is too long to go into here. What we do know is that

by the time of the mid-17th century Civil Wars between King and

Parliament England had seen a weakening of the established Anglican Church,

attacked by Puritans for what they saw in it as remnants of Roman Catholicism

and hints of papistry.

Portrait of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) after the work of the English miniaturist Samuel

Cooper (1609-1672). Next to it is a stone image of Cromwell, one of the small heads of kings

and queens of England around the outside of St Mary’s Church, Bicton, a few miles from Budleigh Salterton. It is

ironic that the image appears on a High Anglican church, but the Cromwell

Association believes that ‘without doubt it is Cromwell’s face which is represented’

The English Civil Wars of the mid-17th century between Royalists and Parliamentarians ended with the trial and execution of King Charles I, and the establishment of the government known as the Commonwealth, with the Puritan Oliver Cromwell at its head.

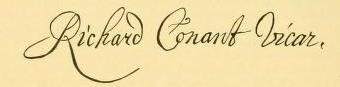

A list of vicars of East Budleigh on display

in All Saints’ Church, East Budleigh. An earlier version on display in the church included the word 'French' after Daniel Caunieres' name

Cromwell’s

government appointed Commissioners to remove, in the words of the Ordinance

of 28 August 1654, ‘divers scandalous and insufficient Ministers and

Schoolmasters in many Churches, Chappels and Publique Schools within this

Nation’.

An undated guide book for All Saints’ Church, published

by All Saints Parochial Church Council, tells us that Stephen Chapman had been ejected

by the Parliamentarians after being ‘so much harassed by them that he was

forced to quit the living’ and that the new vicar ‘was regarded as a usurper by

the congregation’.

Divines in a bit of a ding-dong: The title page of the 1713 book by the Rev Edmund Calamy (1671-1732), left, about the sufferings of nonconformist clergy

during the Restoration inspired the Rev John Walker (1674-1747) to compose a similar work, published the following year, showing

how Anglican clergy had endured persecution under Cromwell

There is no evidence for the statement that Francis Wilcox was regarded as a usurper. The assertion that Stephen Chapman was harassed by Parliamentarians was based on text from the Rev John Walker’s 1714 book Sufferings of the Clergy, itself a riposte to the earlier publication by the Rev Edmund Calamy. Both books were part of the propaganda campaign waged between High Anglican and nonconformist writers in the early 18th century. Walker’s book was criticised by the Protestant clergyman John Lewis as ‘a farrago of false and senseless legends’.

The latest edition of the All Saints guide book

does not include the ‘usurper’ reference.

King Charles II (1630-1685) in Garter robes by the Anglo-Scottish artist John Michael Wright (1617-1694). Image credit: National Portrait Gallery-Wikipedia

Following the 1654 ejectment of ministers

like Stephen Chapman by the Parliamentarians a second ejectment took place in

1662. This time it was the turn of ministers with Puritan tendencies to be removed

by the government. Cromwell had died in 1658, to be replaced as ruler two years

later by King Charles II in what became known as the Restoration.

A copy of the

Book of Common Prayer, printed at Cambridge in 1662 by John Field (died 1668) Image credit: Boston MA Public Library.

The so-called Cavalier Parliament

with its overwhelmingly Royalist inclinations saw an opportunity to rid the Church

of England of clergy with unacceptable beliefs.

Puritanism had established particularly deep roots in Devon. It was the county in 1662 with the largest number of ejected ministers - 121 in total, the only other county to approach it being Yorkshire with 110.

Vicar’s Mead, on Hayes Lane, East Budleigh. It is here that the young Walter Ralegh and Roger Conant (c.1592-1679) may have received their early schooling from the vicar

Francis Wilcox kept his place at East Budleigh. He remained as vicar for four years during the Restoration in spite of having been appointed under the Cromwell regime, because he apparently took the oath of uniformity. He resigned in 1664, going on to succeed his father as rector of Powderham the following year.

Not

all ministers with Puritan tendencies became nonconformists. Moderates felt

able to accept Anglican rituals; others were ambitious to develop their careers

or simply needed a living because they lacked private means. Some ministers who

had become deeply involved in the religious life of their community would have realised

that by becoming dissenters and excluding themselves from any influence in

their parish they would no longer be able to share with their parishioners the

essential Protestant beliefs that they held.

Francis Wilcox was

succeeded in 1664 by Henry Evans, an East Budleigh vicar with even stronger Puritan

links, though he would evidently have taken the oath of uniformity.

Dr Thomas Nadauld Brushfield (1828-1910) in the library of his house ‘The Cliff’ in Budleigh Salterton. The commemorative blue plaque was erected in 2017

From

research into the history of All Saints’ Church by Budleigh’s antiquary Dr Brushfield,

we know that Henry Evans was a student at New Inn Hall, Oxford from 25 March 1655

to 16 August 1658, gaining a Bachelor of Arts degree. He was awarded a Master

of Arts degree on 15 June 1661.

Copper engraving with hand colouring of New Inn Hall, Oxford, by the English artist George Hollis (1793-1842), published by J. Ryman, Oxford, in 1836

New

Inn Hall was regarded as a notoriously Puritan college of Oxford.

Portrait of Christopher Love (1618-1651) by the Flemish engraver Michael Vandergucht (1660-1725), from the collection of the National Library of Wales

Another celebrated student tutored by Christopher

Rogers at New Inn Hall was the Welsh Presbyterian preacher Christopher Love who

was executed by the English government in 1651 and revered by Puritans as a

martyr.

Richard Conant’s signature as reproduced in the History and Genealogy of the Conant Family in England and America by Frederick Odell Conant (1856-1928), published in 1887

On

17 July 1672, three months after the death of the Rev Henry Evans, All Saints’

Church welcomed a new vicar with a familiar name. And even more interesting Puritan

links!

As Dr Brushfield pointed out, the Rev Richard Conant is believed to have been the only vicar of East Budleigh who was born in the parish. The nephew of Roger Conant, founder of Salem, he was born in East Budleigh in 1622 to Richard and Jane Conant née Slade.

The clerical tradition was prominent in the Conant family. Richard Conant – Roger’s father – had been a churchwarden at All Saints’ Church just as Sir Walter Ralegh’s father had been. Three Conant family members served as ministers of religion.

Forde Abbey, near Chard, Somerset, home of Sir Henry Rosewell (1590-1656), and later of Edmund Prideaux (1632-1702) Image credit: Wikipedia

The Rev John Conant – Richard’s uncle and Roger’s brother – had been a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, before being instituted on 30 December 1619 as Rector of Lymington, near Ilchester in Somerset. The rectorship was in the gift of Sir Henry Rosewell, a Puritan who was prosecuted for holding services in the private chapel of his home, Forde Abbey.

A painting by the English artist John Rogers Herbert (1810-1890) of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, of which John Conant (1584-1653) was a member. Image credit: Wikipedia

In

1643 John Conant was appointed member of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, a council of theologians

and members of the English Parliament with the aim of restructuring the Church

of England. ‘Many things remain in the Liturgy, Discipline and Government of

the Church, which do necessarily require a further, and more perfect Reformation

than as yet hath been attained,’ read the Ordinance of 12 June 1643 which

called for the Assembly to take place. It was a clear questioning of the very

foundations of Anglicanism.

King Charles I (1600-1649) by a follower of the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), a version of the much copied original in the

Royal Collection, Windsor Castle. Image credit: Wikipedia

King Charles I was naturally unwilling to give his

assent, but his opponents were resolute, as seen in the tone of the Ordinance.

It had been, they stated,

‘Declared and Resolved by the Lords and Commons

assembled in Parliament, That the present Church-Government by Archbishops,

Bishops, their Chancellors, Commissaries, Deans, Deans and Chapters, Archdeacons,

and other Ecclesiastical Officers depending upon the Hierarchy, is evil, and

justly offensive and burthensome to the Kingdome, a great impediment to

Reformation and growth of Religion, and very prejudicial to the State and

Government of this Kingdome’.

Dr John Conant (1608-1694) by an unknown artist. Image credit: Wikipedia

Confusingly, another family member by the name of John Conant was also a clergyman. This was Richard’s cousin, born in Yettington in 1608 to Robert and Elizabeth Conant née Morris. Much of his life was spent in Oxford, where he became Rector of Exeter College in 1649, Regius Professor of Divinity in 1654 and three years later, was appointed by Richard Cromwell as Vice-Chancellor of the University. Following the Restoration he was appointed Archdeacon of Norwich in 1676.

The Crypt of St Anne’s

Church, Blackfriars, London. Painting by the English artist Percy William Justyne (1812-1883). The church

was destroyed during the Great Fire of London in 1666 and was never rebuilt

Roger

Conant himself may have revealed his association with Puritans during his time

as a Salter in London. It was at St Ann’s Church, Blackfriars, on 11 November 1618, that he married Sarah Horton. One might have

expected the marriage to take place at All Hallows’ Church, next to Salters’ Hall in

Bread Street, where most members of the Salters’ Company attended.

William

Gouge (1575–1653) painted by the British artist Gustavus Ellinthorpe Sintzenich (c.1821-1892), Image credit: Wikimedia

But

St Ann’s was known as a Puritans’ church. William Gouge was the minister and preacher for 45 years,

from 1608. He was also a member of the 1643 Westminster Assembly of Divines, as

was Roger’s elder brother John Conant.

View of

Emmanuel College Chapel in 1690 by the British artist David Loggan (1634-1692). Image credit: Wikipedia

Well before he succeeded Henry Evans as vicar of East

Budleigh on 17 July 1672

Emmanuel College window (1884) depicting,

left, John Harvard (1607-1638) the Puritan clergyman founder of Harvard University; next to

him is an image of Laurence Chaderton (1536-1640), a Puritan divine who was the first

Master of Emmanuel College. Image credit: Dolly442-Wikipedia

It has been shown that of 130 men from English universities who took part in the religious emigrations to America before 1646, no fewer than 100 had studied at Cambridge, of whom 35 had been at Emmanuel.

The memorial to William (1569-1621) and Richard Venn (1601-1662) in St Michael’s Church, Otterton. It records how Richard Venn, born in Otterton and instituted as vicar, was ‘ejected from his living in 1645 for his loyalty to his Church and King’. Image credit: www.britainexpress.com

Before he moved to East Budleigh, Richard Conant was probably living in Otterton according to Dr Brushfield. The Parliamentary Committee set up to eject ministers considered unsatisfactory following the defeat of the Royalists in the English Civil War evidently felt that he was a more suitable vicar than Richard Venn, the previous incumbent. Richard Conant was officially appointed by an order of 2 May 1646, replacing poor Venn who ended up being kept a prisoner for almost a year in spite of his advanced age.

St Michael's church, Otterton.

The late 11th century tower was part of Otterton Priory. Image credit: Chris Allen

Under

the Restoration it was the turn of the Puritan Richard Conant to be ejected

from the Otterton ministry.

To be appointed as vicar Richard Conant must have signed

the oath of conformity, but had he really embraced the Church of England with its

rituals, so many of which Puritans found offensive? Or perhaps, as moderate Puritans, both he and

the Rev Henry Evans whom he would succeed as vicar had come to some kind of acceptance

of Anglicanism.

They may well have had regular contact with other nonconformist ministers who had been ejected in 1662. The Act of Uniformity which Parliament passed that year did not succeed in uniting England in religious practices. Parishioners in many East Devon communities remained loyal to their ejected ministers. Before they were allowed their own places of worship they would meet with them, as in the case of Axminster, ‘in houses and woods, barns, and obscure and solitary places’. In East Budleigh, it is said that before Salem Chapel was built, Dissenters met secretly in a barn in Frogmore Road.

Two Dissenters’ places of worship in East Devon:

(top) Ottery St Mary’s ‘Church of Christ of Protestant Dissenters’ dates from

1688, and is one of the

oldest non conformist churches in England. A grade II listed building, it is

now part of the United Reformed Church; below is Loughwood Meeting House, an

historic Baptist chapel, one mile south of the village of Dalwood. There was a

meeting house on this site in 1653, although the current building may date from

the late 17th century or early 18th century. It is one of the earliest

surviving Baptist meeting houses. Since 1969 it has been owned by the National

Trust. Image credit: Robin Drayton and www.geograph.org.uk

In Woodbury, the Rev Samuel Fones, ejected as vicar after 16 years of service, was so well loved by parishioners that his congregation was reported to have wept as he climbed to the pulpit to preach his final sermon. However he did not immediately leave Woodbury and apparently gathered round him a small group of sympathisers who met at his house.

Samuel Fones’ reformist leanings are well documented. He had graduated at New Inn Hall, the notoriously Puritan college of Oxford where East Budleigh’s conformist vicar, the Rev Henry Evans, had been a student.

John Winthrop (1588-1649), uncle of the Rev Samuel Fones (died 1693), in a painting by an unknown

artist thought to be by a follower of Anthony van Dyck, donated to the American

Antiquarian Society. Image credit: Wikipedia

More significantly, he was a nephew of John Winthrop, the English Puritan lawyer who was one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of colonists from England in 1630 and served as governor for 12 of the colony's first 20 years. His writings and vision of the colony as a Puritan ‘city upon a hill’ dominated New England colonial development, influencing the governments and religions of neighbouring colonies. Samuel Fones eventually followed his uncle to New England, where he died in 1693.

Ministers who had been appointed during the Interregnum

of 1649-1660 like Richard Conant and Samuel Fones may well have proved

effective in promoting non-conformity because of their mobility. They were willing

and able to visit other parishes in order, as it

has been said, ‘to keep alive the flame of their idea of godly worship’.

Portrait of Bishop Seth Ward (1617-1689) by the English painter John Greenhill (1644-1676). Image credit: Wikipedia

Whatever Richard Conant was doing in those 12 years before he became vicar of East Budleigh in 1672, there is no doubt that there was keen official awareness of the growth of nonconformism. The diocese of Exeter was an area of particular tension because of what has been described as the aggressive policy of uniformity pursued by Seth Ward, its bishop from 1663 to 1667.

On 16 January 1664, two years after Parliament’s passing of the Act of Uniformity, Bishop Ward wrote to Gilbert Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury, complaining of more than 20 ejected ministers in Exeter alone who had ‘nothing els to doe but to be gnaweing at the root of Governmt and religion, and to that purpose have many secret meetings and conventicles’.

Even worse, sympathetic officials seemed to

be conniving at their subversive activities. ‘Those who are the Sage and the

Wise amongst our friends, winke at them and thinke it by no means fit to

discourage them,’ admitted the Bishop.

Gulliford Burial Ground on Meetings Lane, Lympstone; the name of the location is the only reminder that there was a Dissenters’ chapel here, first built in 1687

And

yet at a personal level, many officials of the Church of England would have

maintained a cordial relationship with nonconformist clergy. There were some

outstandingly learned men amongst the ejected ministers. A good example was Exeter-born

Samuel Tapper,

Following his Bachelor of Arts degree, which he took in

1654 at Exeter College, Oxford, Samuel Tapper continued his studies with the

intention of taking a Master’s degree. However ill-health forced him to return

to Devon, where he served as minister in a number of parishes until the

Restoration. He then settled in Exeter. Here, according to Calamy, in spite of

having been one of the ejected ministers, he benefited from ‘the intimate

friendship of the most valuable and learned clergy’ including John Wilkins,

later Bishop of Chester, and Ezekiel Hopkins, who became Bishop of Derry.

Even Seth Ward, Calamy tells us, was no exception. Tapper often dined at the Bishop’s Palace: ‘and the Bishop told him, the oftener he came the more welcome.’ The issue of his nonconformity seems to have been a subject of friendly teasing rather than bitter enmity for Seth Ward. To quote Calamy again: ‘Once and again hath that Learned Prelate laid his hands on Mr. Tapper’s Head, and bless’d him: And then would smilingly say, Mr. Tapper where is the Harm of a Bishop’s laying on of Hands?’

So esteemed were his sermons that the Treasurer of Exeter Cathedral, Baldwin Ackland persuaded Bishop Ward to let Tapper preach there on condition that the liturgy was read by another person: ‘and the Bishop took no notice, till the repeated Clamour of some of the furious Gentry oblig’d him privately to desist; which he did.’

Bishop Seth Ward, of course, was as learned in his way

as Samuel Tapper. A mathematician and astronomer, he was one of the original

members of the Royal Society of London.

As for his response to the Oath of Uniformity of 1662,

Samuel Tapper was apparently prepared to conform, being ‘no Enemy to

Episcopacy, or a Liturgy’. However, he would say that he was, in Calamy’s words,

‘not prepar’d to assent to a Book which he could not possibly see, before his

Assent was requir’d’.

Later, as minister at the Gulliford chapel, what was

described as his ‘practical warm preaching and holy exemplary conversation’

made him hugely popular with his congregation.

Dr Brushfield tells us

that Richard Conant was an excellent vicar of East Budleigh: ‘He held the living for 16½

years, and was a hardworking, painstaking and exemplary clergyman: that he had

good business habits is shown by his management of the various charities, about

which there had been previously much laxity.’

We

also know that however conformed he may have been as a vicar, he apparently retained

his Puritan leanings till the end of his life.

Portrait of Richard Baxter (1615-1691), after the English artist Robert White (1645-1703), in

the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. Image credit: Wikipedia

On

his death in 1688, Richard Conant left in his Will to his daughter and to his

sister two books written by a theologian described as one of the most

influential leaders of the nonconformists. Richard Baxter (1615-91) was a

Puritan who spent time in prison for his beliefs. Yet he was described by

Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, the 19th century Dean of Westminster, as ‘the

chief of English Protestant Schoolmen’ and he is remembered in the Church of

England with a commemoration on 14 June every year.

The title page of A Saint or A Brute by Richard Baxter

To his daughter, Mary Mercer, Conant left his copy of Baxter’s book A Saint or A Brute, which had been published in 1662. The essence of this work is contained in Baxter’s words: ‘I undertake to prove, that the reasons for Godliness are so sure, and clear, and great, that every one must be A SAINT OR A BRUTE. He that will not choose a life of HOLINESS, hath no other to fall into but a life of SENSUALITY.’

The title page of The Life of Faith by Richard Baxter

A mention in the Will of a second book by Baxter is

interesting in that we learn of another Conant family member who followed her

uncle Roger in crossing the Atlantic to settle in Massachusetts. Richard Conant’s

bequest was ‘To my dear sister Mrs Mary Veren of Salem, in New England (if she

be living at the time of my decease)’.

The book was The Life of Faith, or A Treatise of the Holy and Happy Life of Sincere Believers, a massive tome of 970 pages. The work, published in 1670, was in three parts: ‘A sermon preached to King Charles II, based on Hebrews 11:1, with another sermon appended to it, for further clarification’; ‘Instructions for confirming believers in the Christian faith’; and ‘Directions on how to live by faith, or how to exercise it upon all occasions.’

Five years older than Richard, Mary Conant was the

wife of Hilliard Veren, who had migrated to New

England in 1635 on the ship James with his parents and siblings. The couple

had married on 12 April 1641 in Salem, where they settled.

There is no evidence that

Richard Conant enjoyed a cordial relationship with a Bishop of Exeter, similar

to the one that Samuel Tapper had had with Seth Ward. Yet the Conant family

must have been well known to diocesan officials. Both Ward and Samuel Tapper’s friend

John Wilkins, the future Bishop of Chester were acquainted with Richard’s cousin,

the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, Dr John Conant. In 1659, they had

accompanied him to London to

help thwart the grant of a university charter to Durham College.

However, by 1672 when Richard

Conant became vicar, Seth Ward had moved on to become Bishop of Salisbury.

Anthony

Sparrow (1612-1685), Bishop of Exeter from 1667 to 1676, by an unidentified painter. Image credit: Wikipedia

He was succeeded as Bishop of Exeter in 1667 by Anthony Sparrow, who has been described as one of the so-called Caroline Divines – 17th century Anglican theologians who opposed the Puritans and supported the divine right of kings.

The best known of them was

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was executed in 1645, having been

accused of treason by Parliament. Supported by King Charles I, Laud and his

followers were part of a reform movement within the Church of England in the

early 17th century. In theology Laudians rejected the predestination

theory advocated by Jean Calvin and Puritans in favour of the doctrine of free

will taught by the Catholic Church.

In their writings their terminology recalled the old traditional Catholic theology rather than the new Protestant theology in which ministers like Richard Conant had been educated. In fact Sparrow has been described as ‘a divine who appeared to flirt with popery’ in view of his belief in traditional Catholic rites such as confession and the sacrament of penance.

Here is part of his ‘Sermon concerning Confession of

Sinnes’ given in 1637, two years after his ordination: ‘He that would be sure

of pardon, let him seeke out a Priest, and make his humble confession to him;

for God, who alone hath the prime and originall right of forgiving sinnes, hath

delegated the Priests his Judges here on earth, and given them the power of

absolution...’

Title page of Richard Baxter’s ‘The Reformed Pastor’. Image credit: Wikipedia

The vast majority of Protestants, by contrast, had consistently

rejected the notion of confessing one’s sins to a priest. ‘I have no doubt that

the Popish auricular confession is a sinful novelty, which the ancient Church

was unacquainted with,’ wrote Richard Baxter in his book ‘The Reformed Pastor’,

published in 1657.

Use of the very

word ‘priest’, particularly in referring to a delegated group with special

powers, had offended most Protestant theologians; they preferred the word ‘minister’.

A 1722 edition of Bishop Sparrow’s A Rationale upon the Book of Common Prayer’

But here is Bishop

Sparrow, in a section entitled ‘Of the word Priest’ in his book ‘A Rationale upon the Book of Common Prayer’ defending it in the year that

Richard Conant became vicar of East Budleigh: ‘That name by which S.

Paul calls them, may not only lawfully, but safely, without any just ground of offence

to sober men, be used still by Christians, as a fit name for the Ministers of

the Gospel,’ he wrote, ‘and so they may be still called, as they are by the

Church of England in her Rubrick, Priests.’

Where Puritans wanted

their places of worship to be meeting houses devoid of ornamentation Laudians believed

in what they saw as ‘the beauty of holiness’: churches should be decorated with stained

glass and statues, the altar should be raised and revered as a sacred place and

priests should wear elaborate vestments.

At St Swithun’s Church in Woodbury, a few miles from East

Budleigh, an attempt was made in 1640 to implement Archbishop Laud’s rulings:

the Elizabethan communion rails were set

up on three sides of the altar to separate it from the congregation. Later,

they were removed and placed around the font.

Under the Restoration, English bishops, most of whom were Laudians, called for making churches beautiful. Churches were ordered to make repairs and to enforce greater respect for the church building. Thus Bishop Sparrow in A Rationale upon the Book of Common Prayer’ writes of ‘the beautiful Doors or Gate’, referring to Acts of the Apostles Chapter 3, Verse 2, ‘because those that had enter’d them, might see the whole beauty of the Church.’

Thomas Lamplugh (1615-1691), Bishop of Exeter from 1676 to 1688. Portrait by the German-born painter Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723). Image credit: Wikipedia

Anthony Sparrow left Exeter in 1676 to be promoted

as Bishop of Norwich.

Given the strong

Puritan tradition of the West Country one wonders how much hostility greeted attempts

to introduce Laudian reforms in East Devon churches like All Saints during the

Restoration.

Portrait

of King James II (1633-1701) by the Dutch artist Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680). Image credit: Wikipedia

Much more likely to have fanned the flames of dissent were the events which took place following the accession to the English throne of the Catholic King James II in 1685. His brother, King Charles II, whom he succeeded, had been suspected by many people of having Roman Catholic sympathies and the extent to which the new king would promote his faith at the expense of Protestantism was a cause for concern for many politicians and ordinary citizens.

James Scott (1649–1685),

Duke of Monmouth, KG, in Garter Robes, after Sir Peter Lely. Collection of the National

Trust. Image credit: Wikipedia

Two months after James II’s coronation in Westminster Abbey, his nephew James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, the eldest illegitimate son of Charles II, claimed the throne. He landed at Lyme Regis in Dorset on 11 June, knowing that as a Protestant he would gain support and recruit an army in the South West of England.

In Colyton, for example, still proud of its reputation as ‘The Most Rebellious Town in Devon’, about 86 men, around a quarter of the total adult male population of the town, joined Monmouth’s untrained and ill-equipped army. Statements taken on the capture of the rebels reveal that they had deep seated convictions.

These men were religious zealots who believed wholeheartedly in Protestantism as a cause. John Sprague, for example, a mason of Colyton, stated that he ‘believed that no Christian ought to resist a lawful power; but the case, being between popery and protestantism, altered the matter, and the latter being in danger, he believed it was lawful for him to do what he did.’

The attempt to overthrow

James II had some notable flaws. The revolt is known as the Pitchfork Rebellion

because many of the insurgents were armed with only their farm tools as weapons.

A major weakness of the rebellion was Monmouth’s failure to rally the gentry to

his cause.

A wounded supporter of Monmouth taking refuge in a hay barn after the battle by the English artist Edgar Bundy (1862-1922). Image credit: Wikipedia

On 6 July 1685 the

last battle on English soil was fought at Sedgemoor on the Somerset Levels.

Monmouth’s forces were decisively routed by the Royalists’ professional army.

The subsequent

Bloody Assizes, presided over by Judge Jeffreys and commencing at Winchester on 25 August 1685,

People in East Budleigh would

certainly have learnt of Monmouth’s activities and had news of his defeat, but

only one rebel from the area is recorded: a certain John Chamberlaine.

Brass coffin plate of Richard III Duke (1567 – 19 April), lord of the manor of Otterton, now affixed to the west wall of St Michael's Church, Otterton, affixed to his coffin within the Duke family vault in the church. Image credit: LobsterThermidor- Wikimedia

Some more brass coffin plates of the Duke family on the west wall of St Michael’s Church, Otterton. The central plate is that of Richard VII Duke (1688-1740), who succeeded to the lordship of Otterton Manor on the death of his cousin Richard VI Duke MP (1652-1732)

A much more significant link between the Budleigh area and Monmouth’s Rebellion lies in the person of Richard VI Duke, husband of Isabella, née Yonge, lord of the ancient Manor of Otterton, next to East Budleigh, and advowson or patron of All Saints’ church with the right of appointing its vicar.

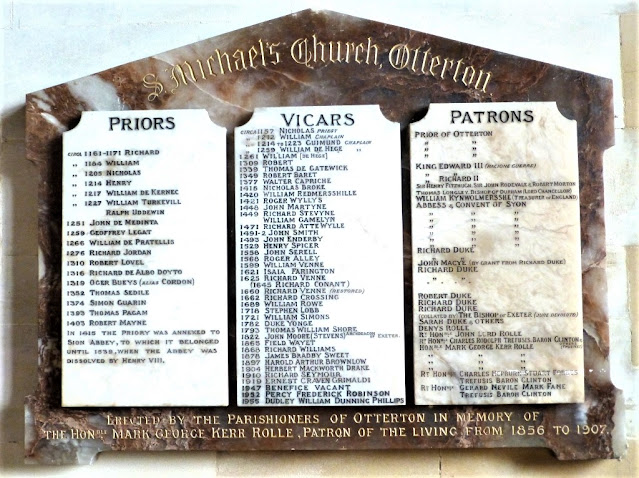

On the south-east wall of St Michael’s Church is this marble monument with tablets showing Priors, Vicars and Patrons of Otterton, including among the latter Richard Duke MP and his father Richard Duke (1627-1716)

His father, Richard Duke, husband of Frances, née Southcote, fought for Parliament in the Civil War and was described as insisting on ‘reading prayers himself in the Presbyterian way’. As a Member of Parliament, Richard Duke represented Ashburton four times, in 1679, 1695, 1698 and 1701. His wife Isabella, born in 1650, was the sister of Sir Walter Yonge, a similarly wealthy landowner who was the Member of Parliament for Honiton. Bishop Seth Ward, during his time at Exeter had complained in a letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury that there were at least 14 Justices of the Peace ‘who are accounted arrant Presbyterians’, among them Sir Walter Yonge.

Remains of what used to be the residence of the Duke family. Image credit: Sarah Charlesworth; Wikipedia

The family of Richard Duke, the Member of Parliament, owed its fortune to an earlier Richard Duke who had bought the Manor of Otterton with the advowson at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII. He used the site of Otterton Priory to create a new home known as Otterton House or the Manor House, built in the form of a quadrangle. Born around 1515, he died in 1572.

The Duke family arms are sculpted in stone on the porch above the door – all that remains of the family home

He became Member of Parliament for

Weymouth in 1545 and for Dartmouth in 1547 and Sheriff of Devon in 1563–64,

positions which gave him an advantage in bidding for ex-monastic lands.

Ralegh’s letter, written in 1584 to Richard Duke II (died 1607). A copy is in Fairlynch Museum, Budleigh Salterton

It was his nephew and heir, Richard Duke II, who refused to sell Hayes Barton to Sir Walter Ralegh in 1584. His refusal is evidence of the Duke family’s power and prestige at a time when Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite was at the height of his influence.

In the summer of 1680 Monmouth

had undertaken a tour of the West Country during which he had made obvious

efforts to cultivate wealthy landowners and others who might support him in his

claim to the throne.

On 31 August, he was in Otterton where he was welcomed by Richard Duke.

All that remains of Great House, on South Street, Colyton, seat of the Yonge family, and home of Sir Walter Yonge (1653-1731). Image credit: Roger Cornfoot; Wikipedia

The day before, he had been entertained at the Great House in Colyton, home of Richard Duke’s brother-in-law Sir Walter Yonge.

Forde Abbey, bought in 1649 by Edmund Prideaux (died 1659) Attorney General to Cromwell and father of the Edmund Prideaux (1634–1702) who entertained the Duke of Monmouth there in 1680. Image credit: Sarah Smith; geograph.org.uk

He also spent

one night at Forde Abbey in Dorset, the palatial home of Edmund Prideaux, Member of Parliament for the constituency of Taunton.

The visits were evidently recorded by government agents suspicious of Monmouth’s motives and five years later they acted, having received intelligence regarding preparations for the invasion.

Richard Duke was arrested for ‘dangerous and seditious practices’ and a warrant was issued for the arrest of his brother-in-law on 19 May, a month before the landing at Lyme Regis.

Escot in 1794, when about to be sold by Sir George Yonge, 5th Baronet (1731–1812), grandson of the builder Sir Walter Yonge (1653-1731). Watercolour by the clergyman and antiquary John Swete (1752-1821). The house was destroyed by fire in 1808; building started on a new house in 1837. Image credit: Wikipedia

There is a tradition, as related by the Devon-born antiquary the Rev John Swete in his Journals that Monmouth was secreted in Yonge’s Great House at Colyton following the landing at Lyme Regis. Among those put to death, according to Swete, were workmen engaged in the building of Yonge’s new mansion of Escot House. The story was confirmed by Sir George Yonge, the 5th Baronet, writing in 1793 on the subject of Judge Jeffreys’ that the men were ‘hanged at a crossway about a mile from Escot, as a specimen of his goodwill, or rather of his suspicions of my grandfather’.

Like Yonge, Richard Duke was attracted by the

idea of building a new mansion house in Otterton Park. He got as far as

erecting pillars for the gates to hang on. They are still visible on the road

which runs high above the east bank of the River Otter. He planted an

avenue of trees to form the drive, some of which are still standing.

Also arrested in May, prior to Monmouth’s landing, was Thomas Reynell (1625-1698), another wealthy Devon landowner and Member of Parliament who was described after the Restoration as ‘an arrant Presbyterian and a very dangerous Commonwealth-man’. Edmund Prideaux was arrested on 19 June, a report having been received in London that he had given horses and arms to the rebels.

Released in November 1685, Yonge made arrangements to travel abroad with his sister-in-law Elizabeth, a widow since 1673 following the death of her husband Francis Yonge. His brother-in-law and business partner Richard Duke joined them along with Richard’s wife Isabella. Also in the group was their friend John Freke, a lawyer who had come to the attention of the authorities as early as 1676, when a warrant issued on 28 May directed the constable of the Tower of London to hold him ‘for high treason, close prisoner’. In July 1683 he had been summoned in connection with the Rye House Plot. Two years later, on 19 May 1685, Freke’s name had appeared on an arrest warrant along with Richard Duke’s because of the threat posed by the supporters of the Duke of Monmouth.

Portrait of John Locke FRS (1632-1704) by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Image credit: Wikipedia

In

the summer of 1685 the group travelled to Holland where they visited the

physician and philosopher John Locke, a figure who would become one of the most

celebrated and influential thinkers of his time, often known as ‘the father

of Liberalism’. In 1668 he had been elected as one of the early members of the Royal Society. The following century would see his ideas taken up by American

revolutionaries; his contributions

to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United

States Declaration of Independence.

In

1683, two years before Monmouth’s Rebellion, Locke had fled to Holland,

supposedly in fear of his life because of implication in the Rye House Plot to assassinate Charles II and his brother the

Duke of York, later James II.

Portrait of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st

Earl of Shaftesbury (1621-1683) by the English artist John Greenhill (c.1644-1676). Image credit:

Wikipedia

Locke’s medical skills had brought him to

the attention of Anthony Ashley Cooper, appointed Lord Chancellor in 1672 and 1st

Earl of Shaftesbury the following year.

Headed by Shaftesbury, the Whigs began as a

political faction that opposed absolute monarchy and supported constitutional

monarchism and a parliamentary system.

Locke had fled into exile in Holland later that year. It is thought that in the 17th century more books were printed in Holland than in all other European countries put together, and Yonge was apparently keen to have Locke's advice in buying books from Dutch booksellers to furnish the library for his new house at Escot, but it has been said that their conversation was not confined to the choice of books for the new library.

Title page from the first edition of Two Treatises of Government, dated 1690. Image credit: Wikipedia

Locke is justly celebrated for refuting the

theory of the divine right of kings and arguing that all persons are endowed

with natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

Such radical ideas, including the question of loyalty to James II, would have been the subject of discussion between Locke and his group of visitors in the summer of 1685. The idea has been put forward that the chief actors in what has been called ‘Locke’s circle’ were in fact Sir Walter Yonge and Richard Duke, along with Edward Clarke, the Member of Parliament and Recorder for Taunton and the Devon-born physician, magistrate and philosopher Richard Burthogge.

Correspondence

between Locke and the Dukes was maintained long after the visit to Holland. The

Bodleian Library at Oxford University has a collection of letters to Locke from

his friends, including 30 from Isabella Duke written between 1686 and 1693.

Title page of

the first edition of A Letter Concerning Toleration, published in 1689. Image

credit: Wikipedia

John Locke is also celebrated for his advocacy of religious toleration. It has been pointed

out that the reason for this could have been his exile in Holland, where religious issues were discussed more freely and

with less danger than in any other country of 17th century Europe. The

Dutch were a nation which encouraged freethinkers and dissenters.

A step towards religious freedom

as envisaged by Locke was taken when James II issued the Declaration of

Indulgence for Scotland and England on 12 February and 4 April 1687

respectively. The Declaration suspended penal

laws enforcing conformity to the Church of Scotland and the Church of England

and allowed people to worship in their homes or chapels as they saw fit. It

also ended the requirement of affirming religious oaths before gaining

employment in government office.

The Declaration granted toleration to the various Christian denominations, Catholic and Protestant, within the kingdoms but was opposed by Anglicans. Many of them, along with nonconformists, saw it as part of James II’s plan to reintroduce Catholicism.

The English

Declaration of Indulgence was reissued on 27 April 1688, leading to open

resistance from Anglicans.

Evidently James saw the Declaration of Indulgence

as a means of encouraging his fellow-Catholics to return from abroad, but a major

result was the influx of Huguenots. It’s been noted that relatively few had

arrived in the immediate aftermath of the Revocation, but in 1687 they arrived

in large numbers.

Portrait of the Welsh judge George Jeffreys, 1st

Baron Jeffreys (1645-1689), attributed to the British artist William Wolfgang Claret (died 1706). Image

credit: Wikipedia

In the West Country, to awareness of the sufferings of the Huguenots in France was added the bitterness and anger of people aroused by Judge Jeffreys’ Bloody Assizes in the aftermath of Monmouth’s Rebellion, which had been suppressed by a royalist army in July 1685.

From lists of rebels compiled in preparation for the trials it appears that 62 men from Honiton took part in the uprising in addition to 75 from the surrounding parishes of Combe Raleigh, Upottery, Sheldon and Luppitt.

Hostility

to the government of James II was extreme. The king’s agents reported that the

corporation or local governing body

The Bloody Assizes, the Declaration of Indulgence, attempts to introduce Laudian reforms into churches and the Catholic faith of James II all combined to make most East Devon towns into hotbeds of nonconformity. In Honiton, the agents continued, ‘The majority of the town are dissenters, and the whole town against their magistrates.’ The population was ‘unanimous to choose right men’ to represent it, and among these men the agents’ report named Sir Walter Yonge and Edmund Prideaux.

The Trial of the Seven Bishops by the English painter John

Rogers Herbert (1810-1890). Image credit: Wikipedia

Seven bishops opposed James II's 1687 Declaration of Indulgence and as a

result were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London on charges of seditious

libel. The bishops said that whilst they were loyal to King James II, their

consciences would not agree to allowing freedom of worship to Catholics even if

it were to be within the privacy of their own homes as the Declaration proposed,

and thus they could not sign. They were tried and acquitted by a jury on 30

June 1688 to popular rejoicing.

That event and the earlier announcement

on 10 June that Queen Mary of Modena had given birth to a son, a Catholic heir to the English throne, have been seen as

key factors in what has been called the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

A statue

of King William III (1650-1702) at Brixham, where he landed on 5 November 1688. Image credit:

Steve Daniels; www.geograph.org.uk; Wikipedia

On 5 November, William of Orange with

a Dutch army landed at Brixham in South Devon.

Bishop Thomas Lamplugh responded to the news with

an address exhorting the country to remain loyal to King James, and then, abandoning

the Bishop’s Palace in Exeter fled to London. According to the Victorian historian

Lord Macaulay, the king responded to Bishop Lamplugh’s declaration of loyalty

with the words ‘My Lord, you are a genuine old Cavalier’ and rewarded him with

the Archbishopric of York.

Sir Jonathan Trelawny (1650-1721), Bishop of Exeter from 1689-1707, by a follower of

the artist Sir Godfrey Kneller. The painting is part of the Collection of the Bishop’s

Palace, Exeter

Trelawny’s appointment as Bishop of Exeter in 1689 is significant in the story of East Budleigh’s Huguenot refugee, for it was on 24 May of that year that Daniel Caunieres was appointed vicar of All Saints’ Church.

St Mark's Church, Bristol, west front. Image

credit: NotFromUtrecht - Wikipedia

As Bishop of Bristol, Trelawny had encouraged Huguenots in the city to found their own church what is now known as the Lord Mayor’s Chapel, on College Green. Support by English bishops for the Huguenot immigrants was particularly vital when they were proposed as ministers of the Church of England. They were foreign, after all, speaking with a strange accent and perhaps difficult to understand for some parishioners! No doubt sympathetic bishops like Trelawny would have pointed out to objectors that the refugees had suffered for their Protestant faith and that many of them would have been more knowledgeable of the Bible than most members of English congregations.

In any case, the presence of French Protestants in nonconformist groups was not unknown. At least three families of Huguenot refugees had joined the Loughwood Baptists at Dalwood as early as 1657.

Suffering for their Protestant faith was something that East

Budleigh’s parishioners would have understood only too well in the aftermath of

Monmouth’s Rebellion. The year in which Caunieres was appointed saw the

publication of a mass of pamphlets and other writings inspired by the Bloody

Assizes.

Six collections of the dying speeches of those executed in the previous decade for their defence of Protestantism and English liberties were printed in the spring and winter of that year.

The title page of the biography of Judge Jeffreys by John Dunton (1659-1733), from the 1689 edition. Similar material was produced by the Whig pamphleteer John Tutchin (c.1660-1707)

As a reward for his services, Jeffreys had been created Lord Chancellor by James II. Following the Glorious Revolution and the king’s flight into exile, he had been arrested and incarcerated in the Tower of London, where he died in April 1689.

Dunton’s book and the pamphlets and poems of people like the journalist John Tutchin, who had been involved in the Monmouth Rebellion, did much to create a ‘Western martyrology’, following in the tradition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Here, for example, in Dunton’s Life of Jeffreys, is the saintly portrayal of Samuel Potts, a surgeon in Monmouth’s army and one of the four men executed at Honiton, ‘who behaved himself with that extraordinary Christian Courage, that all the Spectators were almost astonished: he being but young about twenty, his Prayers being fervent, his Expressions so pithy, and so becoming a Christian of greater Age, that drew pity and compassion from all present.’

Another Honiton man, ‘a rude Fellow’ according to Dunton, called for a bottle of wine to drink with his guard just before his execution. ‘Your Cup seemeth to be sweet to you, and you think mine is bitter, which indeed is so to Flesh and Blood,’ he tells the guard in last words worthy of the most eloquent preacher, ‘but yet I have that assurance of the fruition of a future Estate, that I doubt not but this bitter Potion will be sweetn'd with the Sugar of the loving kindness of my dearest Saviour, that I shall be translated into such a State, where is fulness of Joy and Pleasure for evermore.’

Caunieres therefore had the support of his bishop and the

sympathy of his All Saints congregation. In addition, he would have had,

perhaps indirectly, the endorsement of John Locke via the All Saints’ patron

Richard Duke.

Both Duke and Locke knew Caunieres’ homeland well. According to an article by Harry Lane, published by the Otter Valley Association in 2009, Duke spent ten months in France between August 1671 and May 1672. In May the following year, he married Isabella and took an even longer extended holiday with her, staying in Montpellier from September 1673 until April 1675 when he returned to Britain. A further six-month visit to the Continent is recorded in his Notebook.

As for Locke, he had spent four years from 1675 travelling in France as a tutor and medical attendant to the English politician Caleb Banks. Ten years later, while in exile in Holland, he would have come into contact with Huguenot refugees who were flooding into the Low Countries at the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and it was during this period that he was writing A Letter concerning Toleration.

Contact with Huguenots forced to

leave their homeland inspired Locke with the thought that such industrious refugees

deserved to be naturalized citizens. They would be ‘perfect Englishmen as those

that have been here since William the Conquerers days & came over with him’,

as he eventually wrote in the paper ‘For a Generall Naturalization’, prompted

apparently by a parliamentary bill introduced in December 1693. In any case, as

he went on to write, ‘tis hardly to be doubted but that most of even our

Ancestors were Forainers’.

It does not seem unreasonable to suppose that Locke discussed such matters with his friends Richard Duke and Sir Walter Yonge, and that Duke would have been therefore all the more likely to endorse Daniel Caunieres’ appointment as vicar.

A bishop like Jonathan Trelawny in Exeter may even have been concerned by the growing number of Dissenters in Devon parishes, a trend that had certainly not been halted under his predecessor, that ‘genuine old Cavalier’ Bishop Lamplugh. Appointing a true Protestant like Daniel Caunieres might help to stem the flow of faithful away from the Church of England.

Did the strategy work? Caunieres stayed 12 years at

East Budleigh before taking up a living in North Devon. He was succeeded at All

Saints in 1702 by Abraham Searle, about whom I’ve discovered very little.

But perhaps he was not as popular as Caunieres had

been. Historian Victoria Nutt, writing in 2008 for the Historic Chapels Trust about the Salem Chapel, in an

article published by the Otter Valley Association, tells us that its first

known minister, Roger Beadon, ordained in 1709, ‘probably arrived at a time

when the local vicar was no longer accepted by a sizeable proportion of the

local population’.

What we do know is that the number of dissenters

must have continued to grow, because by the time of his death in 1719 they had

succeeded in building their own Salem Chapel on the outskirts of the village.

And this was evidently with the approval of Richard Duke. According to Victoria Nutt's article, the Duke family seem to have contributed a quantity of local stone to build the walls.

By the time of

the 1744 Episcopal Visitation Returns – the process by which bishops of the

Church of England gathered information about their diocese – East Budleigh

seems to have had more than the average number of dissenters. The vicar, Matthew

Mundy declared that there were ‘About a Hundred Families in the Parish; thirty

of which, or near that Number, are Dissenters of the Presbyterian sort’, along with

‘one woman in the Parish supposed to be a Roman-Catholick’.

By comparison, the percentage of dissenting families in various East Devon

parishes as reported by their vicars in that year were: Axminster 20%; Bicton 9%;

Colaton Raleigh 0%; Sidmouth 22%. In Woodbury, 10% of individuals were

dissenters.

The Temple Methodist Church, Fore Street,

Budleigh Salterton, with its commemorative blue plaque erected in 2017. The building is a later version of the original built by James Lackington (1746-1815), and strongly opposed by Lord John Rolle (1750-1842)

Almost a century after the building of the Salem

Chapel in East Budleigh, the retired London bookseller and committed Methodist James

Lackington moved to Budleigh Salterton. In 1812, he resolved to build a church

there, believing that its people were ‘in spiritual destitution and darkness’.

Having purchased the freehold of Ash Villa and its large garden on Fore Street he believed that this would be the ideal location. However he had not reckoned with the determined opposition of Lord John Rolle, East Devon’s principal landowner at that time. None of the tenants of the Rolle estate was permitted to help in any way, and Lackington had to engage a builder from Exeter, and bring all the building materials from outside the area. In retaliation, it is said, Lord Rolle built a Chapel of Ease on Budleigh’s West Terrace, about a hundred yards from Lackington’s Methodist church.

In

the 1820s he was criticised for

inserting a special provision in the leases of properties that he owned, ‘that

the lease shall immediately be forfeited if any preaching be allowed’.

A plaque on the restored Salem Chapel, East

Budleigh

Perhaps Richard Duke’s encouragement and participation in the building of Salem Chapel, in stark contrast to later attitudes of bigotry, can be seen as an expression of the spirit of tolerance for which his friend John Locke was so celebrated.