'Dance around the maypole', by the 16th century Flemish artist Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Image credit: Wikipedia

You can read in this article about someone whom Roger Conant would probably have heard about and possibly may have met. This was the adventurer and colonist Thomas Morton whose liking for the tradition of dancing around maypoles brought him into conflict with the separatist Plymouth Puritans who sailed to America on the 'Mayflower' in 1620.

Morton would have been delighted to know that children in the Devon village of East Budleigh, birthplace of Roger Conant, maintain the tradition on May Day.

Earlier this year, on 1 August, I

was invited along with artist John Washington to give a talk about John’s

wonderful painting of Roger Conant’s 1625 encounter with the Plymouth Puritans’

military officer Myles Standish - shown in the foreground on the right - on Fisherman’s Field, in Gloucester,

Massachusetts.

John and I mentioned Standish as ‘short of stature’. We should of course have referred to him as ‘Captain Shrimp’. This was the colourful and better known epithet famously bestowed on Standish by Thomas Morton.

Like Roger Conant, Morton has made a name for himself in Massachusetts, and further afield in the USA. However he was very different in character from the East Budleigh-born pioneer associated with the city of Salem.

A copy of one of the best known portraits of Sir Walter Ralegh, formerly attributed to Zuccaro but now to the monogrammist 'H' (? Hubbard) and dated 1588. Displayed in All Saints’ Church, East Budleigh, it shows Ralegh in court dress at the height of his favour with Queen Elizabeth I. Ralegh had been appointed Captain of the Guard the previous year

Although supposedly Devon-born, Morton is barely known in

this county. But he cuts a complex and flamboyant figure in the story of

America. I’ve been struck by the ways in which he resembles East Budleigh’s more

famous son Sir Walter Ralegh. This is in contrast to Roger Conant, who was described

by his biographer Clifford Hampton as ‘meticulously honest’ and ‘self-effacing’.

Both Ralegh and Morton were poets of course. In fact Dr Jack Dempsey, historian and editor of Morton’s work, believes that this early colonist can also claim to be America’s first poet in English.

The title page of Ralegh’s Discovery of Guiana, showing the Ewaipanoma, or people 'without heads'. This edition was published by Hulsius Levin in Nuremberg, 1599. Image credit: www.historycollection.com

Morton achieved celebrity status in England, partly as a result of writing a book about the exciting discoveries that he had made in the New World. Ralegh similarly, shortly after his 1595 voyage to South America, had published his ‘Discovery of the large, rich, and beautiful Empire of Guiana’.

Ralegh's book had created a sensation when it appeared in 1596, with its suggestions of the treasure to be found in places like ‘the great and golden city’ known to the Spanish as ‘El Dorado’. Equally fascinating for some readers was the author's mention of extraordinary peoples such as the Ewaipanoma, described by the explorer as ‘without heads’.

An earlier publication backed by Ralegh and composed by his friend and tutor, the scientist Thomas Harriot, was 'A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia' which appeared in 1588.

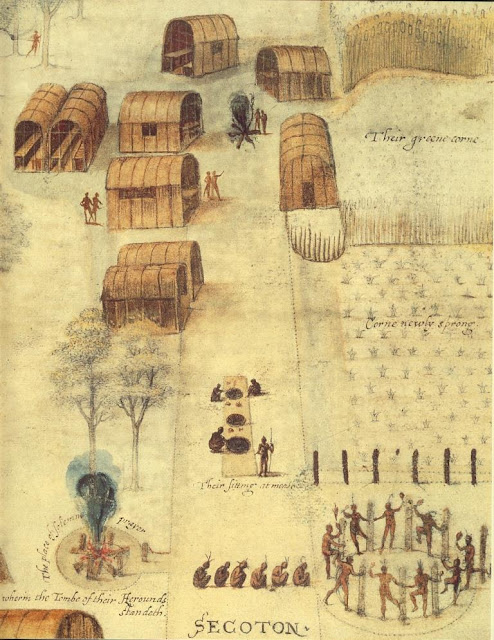

The publisher Theodor de Bry issued a new, illustrated edition in 1590, and it is notable for the remarkable watercolours depicting life in America, including portraits of Native Americans.

Watercolour by John White of dancing Secotan Indians in North Carolina. Image credit: Wikipedia

They were painted by John White, who along with Harriot had been sent by Ralegh as artist and mapmaker for Sir Richard Grenville’s 1585 expedition to the New World. The collection of White’s paintings is one of the treasures of the British Museum. You can see more of them at https://raleigh400.blogspot.com/2018/11/the-watercolours-of-john-white-artist.html

‘Come to this place where everything is neat and tidy and there is food everywhere!’ is the message of John White’s watercolours according to the American author and science historian Deborah Harkness.

Thomas Morton’s ‘New English Canaan’, first published in 1637, as shown above, aimed similarly to promote the New World to Europeans. The American statesman John Adams, in an 1812 letter to Thomas Jefferson, described Morton as wishing ‘to Spread the fame and exaggerate the Advantages of New England’.

Coincidentally, early on in his career, Morton found employment with a friend of Sir Walter Ralegh. This was Sir Ferdinando Gorges, governor of the English port of Plymouth, who had many commercial interests in New England and who would found the colony of Maine.

'The School of the Night' by Ronnie Heeps, painted in 2006. © the artist. Photo credit: Jersey Heritage

Despite being one of Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite courtiers, Ralegh managed to alienate many members of the Establishment who viewed him and his friends with suspicion, particularly with regard to religion. This fine painting by the Scottish artist Ronnie Heeps is based on the notion that Ralegh was the central figure in a group known by the modern name of ‘The School of Night’. The group supposedly included poets and scientists Christopher Marlowe, George Chapman, Matthew Roydon and Thomas Harriot.

There is no firm evidence that

all of these men were known to each other, but speculation about their connections

features prominently in some writing about the Elizabethan era.

In 1592, following Elizabeth’s proclamation against the Jesuits, the rumour of Ralegh’s supposed atheism was spread by Father Robert Parsons, in a document published in response to the royal edict. There was a reference to ‘Sir Walter Ralegh’s school of atheism’ with its supposed ‘diligence used to get young gentlemen to this school, wherein both Moses and our Savior, the Old and New Testament are jested at, and the scholars taught among other things to spell God backward’.

Fr Parsons’ accusation was of course simply Catholic propaganda, but Ralegh’s enemies were quick to take advantage of it.

A commission was set up in 1594 at Cerne Abbas, close to his home at Sherborne Castle, to deal with accusations that Ralegh and his circle of intellectual friends had denied the reality of heaven and hell. He was acquitted, but the accusation of atheism was again raised at his trial for treason in 1603. It is likely that this contributed to the guilty verdict reached by the court, a verdict which made Ralegh’s death sentence inevitable after the failed 1617 expedition to Guiana.

A conjectural

image of Governor William Bradford, produced as a postcard in 1904 by A.S. Burbank

of Plymouth, together with the front page of Bradford’s Journal. Image credit:

Wikipedia

Curiously, identical words were used by Thomas Morton’s enemies when the same accusation was levelled against him in America half a century later. In his memoirs, the separatist Puritan William Bradford (1588-1657), governor of Plymouth colony, villified Morton as a ‘lord of misrule’ who ‘maintained (as it were) a schoole of Athisme’.

Portrait of

Nathaniel Hawthorne by the Salem artist Charles Osgood, together with a page of

‘The May-Pole of Merry Mount’, as it was first published in 1836

The account of Thomas Morton’s downfall at the hands of Myles Standish and the separatist Puritans of the New England Plymouth Colony is well known partly because of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The May-Pole of Merry Mount’. This short work was first published in 1836 before being included the following year in a collection published by the Salem-born author entitled Twice-Told Tales.

Thomas Morton is said to have been born in Devon around 1579, and that assumption has given rise to the theory that the land of his birth influenced his supposed paganism and accounted for his dislike of Puritans.

‘Devon denotes “people of the land” with life-ways different from those of the urbanized East,’ writes Dr Jack Dempsey, pointing out that Devon’s men and women liked their traditional independence, which was why many in the county had taken part in the 1549 Western Rebellion. ‘As time passed, frustrated Protestant “reformers” called the West Country a “dark corner of the land”’.

Some,

like Sir Walter Ralegh’s parents in East Budleigh in the 1550s, would have seen

that supporting the Reformation made political sense during the monarchies of Edward

VI and Elizabeth I. By 1685, far from being reluctant to embrace the new

religion, the South-West of England was a strongly Protestant region, prompting

the Duke of Monmouth to choose Lyme Regis in Dorset as a landing point to start

his ill-fated Rebellion.

The statue of William III, who landed in

Brixham on 5th November 1688. Image credit: Steve Daniels, Wikipedia

Three years later, the Protestant William of

Orange chose Brixham in Devon to launch the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 and

overthrow the Catholic king James II.

The doorway of Clifford’s Inn, London. Image credit: Wikipedia

We have no hard evidence of where Thomas Morton was brought up in Devon, but it seems that he received a sufficiently good education to pursue law studies at Clifford’s Inn, one of the Inns of Court in London. Initially he worked for Sir Ferdinando Gorges in a legal capacity in England, before overseeing the latter’s interests in the American colonies.

The separatist Puritans who sailed in the 'Mayflower' in 1620, frustrated by their failure to bring about reform within the Church of England, had established their New England Plymouth Colony under their governor William Bradford.

Morton is thought by some

historians to have spent an exploratory three months in America in 1622 before

returning to England the following year, complaining of intolerance in certain

elements of the Puritan community as indeed Roger Conant is said to have done.

Later, in his book ‘The New English Canaan’, Morton described how in America he had encountered “two sortes of people, the one Christians, the other Infidels; these I found most full of humanity, and more friendly then the other.”

He returned in 1624 on the ship the ‘Unity’ with his associate Captain Richard Wollaston and 30 indentured servants. They settled on a site which they named Mount Wollaston in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts, and began trading for furs with Native Americans. The Plymouth Puritans soon objected when Morton and his associates began selling guns and liquor to the natives.

Morton’s partnership with Wollaston ended in 1626 when he discovered that the latter had been selling their indentured servants into slavery on the tobacco plantations of Virginia. Encouraged by Morton, the remaining servants rebelled and organised themselves into a free community, forcing Wollaston to flee to Virginia. Morton now became the inspiration for what has been called an almost utopian project, with aims which included a degree of integration into local Algonquian culture.

The seal of the City of Quincy in the US state of Massachusetts, adopted in 1889. Image credit: Wikimedia

The new settlement was renamed as

Ma-re Mount, literally ‘Hill by the Sea’, as shown on the seal of the City of Quincy,

but soon became known as Merry Mount. Morton angered the Puritans even more

when in 1627 he and his group held May Day festivities centered on a maypole.

For centuries, dancing around maypoles had been traditional in much of Europe, but the rise of Protestantism in the 16th century led to increasing disapproval by religious reformers who viewed the custom as idolatry and immoral.

In 1549, the vicar of St Katharine Cree church at Aldgate in the City of London had preached a sermon against 'pagan' maypoles from the open-air pulpit at nearby St Paul’s Cross. The listeners were so fired up by what they heard that they pulled the maypole down, cut it into pieces and then burned it.

Under the rule of Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans in England, the Long Parliament's ordinance of 1644 described maypoles as ‘a Heathenish vanity, generally abused to superstition and wickedness'.

May Day at Merrymount: an illustration from 'A popular history of the United States, from the first discovery of the western hemisphere by the Northmen, to the end of the first century of the union of the states'. (1881) Image credit: Wikipedia

News of Morton’s May Day festivities infuriated the Plymouth Puritans, especially as the Merry Mount colonists were evidently encouraging sexual relations between Europeans and Native Americans. Governor William Bradford, in his ‘History of Plimoth Plantation’, recorded his disgust on learning that they had ‘set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices’. It was, he wrote, ‘as if they had anew revived & celebrated the feasts of ye Roman Goddess Flora, or ye beastly practices of ye mad Bacchanalians’.

Additionally, the growing prosperity of Morton’s Merry Mount colony was seen as threatening the Puritans’ trade monopoly.

Captain Myles Standish, as imagined by Budleigh artist John Washington. Photo credit: Peter Bowler

When even more extravagant May Day celebrations around

an 80-foot maypole took place the following year a military offensive against the

colony was led in June 1628 by the Captain Myles Standish.

Sadly, on this occasion, there was no Roger Conant to act as peacemaker between the two groups. Not that there was any serious resistance from Morton and his companions, being as they were, in Governor Bradford’s words, ‘over armed with drink’.

Thomas Morton of Merrymount arrested by Captain Myles Standish of the Plymouth Colony, a book engraving by C. J. Perret from Otis, James. Ruth of Boston: A story of the Massachusetts Bay colony. New York: American book company, 1910. Image credit: Wikipedia

The maypole was chopped down. Morton was arrested and put in the stocks in Plymouth before being put on trial and marooned on one of the deserted Isles of Shoals, off the coast of New Hampshire. He could have starved to death on the island had it not been for friendly natives from the mainland who supplied him with food. Eventually he was able to escape to England.

When he returned to America he was arrested and appeared before the Massachusetts Bay Court, on 7 September, 1630 before being shipped back to England where he spent a short spell in jail.

Furious with his treatment and supported by Ferdinando Gorges, in 1635 Morton successfully sued the Massachusetts Bay Company, the political power behind the Plymouth Puritans. Two years later, in 1637, he published his three-volume ‘New English Canaan’, a broadside against the Plymouth Puritans.

It was, according to an article published by the New England Historical Society, ‘a witty composition that praised the wisdom and humanity of the Indians and mocked the Puritans’.

The Puritans were, he wrote in the third book, intolerant people who ‘make a great shewe of Religion, but no humanity’. Professing his anger at their mistreatment of native Americans he described occasions when the latter had been cheated, robbed of their land and massacred. The Puritans, he claimed, wished to keep the resources of New England a secret so that they alone could benefit.

‘The New English Canaan’, described in a 2019 article by American writer Matthew Taub as ‘a harsh and heretical critique of Puritan customs and power structures’, not surprisingly enraged Morton’s enemies.

Governor Bradford referred to it as ‘an infamouse & scurillous booke against many godly & cheefe men of ye cuntrie; full of lyes & slanders, and fraight with profane callumnies against their names and persons, and ye ways of God’.

Condemned by the Plymouth Puritans, ‘The New English Canaan’ became what is probably the first book to be banned in what is now the USA.

Rashly, Morton returned once more to America, and was once again arrested. After yet another spell in prison, his petition for clemency was granted. He ended his days in Maine, protected there by Gorges' supporters. He died in 1647 at the age of 71.

For centuries, historians tended to follow Governor Bradford and the Plymouth Puritans in villifying Thomas Morton. Charles Francis Adams Jr, whose edition of ‘The New English Canaan’ was published in 1883 by the Prince Society, wrote him off as ‘a born Bohemian’ and ‘a lawless, reckless, immoral adventurer’.

As for Morton’s colony of Merry-Mount, Adams dismissed it as ‘unquestionably, so far as temperance and morality were concerned, by no means a commendable place’.

In the 20th century, Roger Conant’s biographer Clifford Shipton referred disparagingly to Morton as ‘that jovial scamp’. Yet a century earlier, Nathaniel Hawthorne had set a very different tone in his version of the story of Morton’s maypole. ‘Jollity and gloom were contending for an empire,’ he had written, contrasting Morton’s ideas with what the Plymouth Pilgrims represented. ‘Not far from Merry Mount was a settlement of Puritans, most dismal wretches, who said their prayers before daylight, and then wrought in the forest or the cornfield, till evening made it prayer time again. Their weapons were always at hand, to shoot down the straggling savage. When they met in conclave, it was never to keep up the old English mirth, but to hear sermons three hours long, or to proclaim bounties on the heads of wolves and the scalps of Indians. Their festivals were fast-days, and their chief pastime the singing of psalms.’

In our modern, liberal era there are those taking a more favourable view of Morton, perhaps inspired by Hawthorne. Wikipedia’s profile of Merry Mount’s founder describes him as a ‘social reformer known for studying Native American culture’, and in recent times there have been plenty of more colourful opinions. ‘Today, people might call him America’s first hippie,’ writes the author of the New England Historical Society’s article quoted above. ‘Had it not been for his May Day party with a giant Maypole, Thomas Morton might have established a New England colony more tolerant, easygoing and fun than the one his dour Puritan neighbors created at Plymouth Plantation.’

American writer Ed Simon, in an article published in The Public Domain Review of 24 November 2020, goes even further. ‘The utopian Merrymount, it has long been argued, was a society built upon privileging art and poetry over industriousness and labor, and pursued a policy of intercultural harmony rather than white supremacy,’ he claims. Where Merrymount stood, now an industrial area, ‘once bore witness to a strange and beautiful alternative dream of what America could have been.’

Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota, United States. This colossal national monument shows (left to right) the sculpted heads of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. Image credit: Wikipedia - Thomas Wolf, www.foto-tw.de

There is a similarly significant view of Morton in Philip Roth’s 2001 novel, 'The Dying Animal', quoted by historian Peter C. Mancall:

'Our earliest American heroes were Morton’s oppressors, Endicott, Bradford, Miles Standish. Merry Mount’s been expunged from the official version because it’s the story not of a virtuous utopia but of a utopia of candor. Yet it’s Morton whose face should be carved in Mount Rushmore.'

Nine years earlier, in 2011, Governor Deval Patrick proclaimed May 1 Thomas Morton Day in Massachusetts, recognizing Morton’s achievements. You can see the proclamation here, as reproduced online by Dr Jack Dempsey, who has produced a modern edition of 'The New Canaan'. For many Americans, the event was long overdue: it had been planned, as Dr Dempsey writes, ‘in honor of this intrepid and good-humored Englishman who made a success of his trading post by treating Native Americans with respect’.

Thornton in 1870. Image credit: Wikipedia

Did Roger Conant and his fellow-settlers enjoy similarly good relations with Native Americans? His 19th century biographer John Wingate Thornton evidently thought so on the basis of testimony from the Ipswich-born American clergyman and historian William Hubbard, who is likely to have met and conversed with Conant.

In Thornton’s 1854 work The Landing at Cape Anne, we find a description of how ‘Governor Conant and his associates, in the fall of the year 1626, removed to Naumkeag, and there erected houses, cleared the forests, and prepared the ground for the cultivation of maize, tobacco, and the products congenial to the soil’, Naumkeag being the original Indian name of Salem.

Thornton’s account continues:

‘In after years, one of the planters in his story of the first days of the

colony, said, "when we settled, the Indians never then molested us, but

shewed themselves very glad of our company and came and planted by us, and

often times came to us for shelter, saying they were afraid of their enemy

Indians up in the country, and we did shelter them when they fled to us, and we

had their free leave to build and plant where we have taken up lands."

Going back to the comparison of Thomas Morton and Raleigh, it is interesting to read Anna Beer’s recently published work. She writes in ‘Patriot or Traitor: The Life and Death of Sir Walter Ralegh’ of what she described as ‘the dark underbelly of the English colonial project’.

Historian Anna Beer with Sir John Millais' celebrated painting 'The Boyhood of Raleigh' as exhibited at Fairlynch Museum in 2018

Dr Beer cites John White’s illustrations and Thomas Harriot’s study of the Algonquin language as supporting the view of those who argue that Raleigh ‘respected the culture and people he was intruding on, and sought to understand it and them’. However it’s fair to say that she goes on to point out that this could be construed as a devious ‘soft imperialism’.

But it was very different from the way in which Native Americans would later be treated by European colonists.

There is no evidence that Roger Conant ever met Morton, though he must have heard of the goings-on at Merrymount. I wonder what he would have thought of them. Conant had supposedly left Plymouth finding the separatist Puritans too intolerant. But perhaps he would have felt that Morton had gone too much the other way.

Meanwhile, Ben Crane’s book 'A Feather at the Feast' is due

for publication next year, presenting Thomas Morton as America’s first nature

writer and falconer. We know, as editor Charles Francis Adams Jr pointed out, that

Morton was ‘passionately fond of

field sports’ such as falconry. And so was Sir Walter Ralegh.

Morton’s 'New Canaan', Governor Bradford’s memoirs and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story ‘The May-Pole of Merry Mount’ are all important texts telling us something of the history of America, and I hope to study them more closely. They are all accessible online.