Many books have been written about East Budleigh’s best known historical figure Sir Walter Raleigh. About the village’s other heroic explorer with transatlantic links, understandably not so much! The last biography of Roger Conant, founder of Salem in Massachusetts, was published in 1945.

But still, plenty about him, written by descendants or by Massachusetts historians, has appeared online – including what I am writing now.

Frederick Odell Conant’s massive History and Genealogy of the Conant family in England and America thirteen generations 1520-1887, first published in the late 19th century, is also now digitally available.

What I didn’t expect to find as a source for Roger’s story was an apparently dry-as-dust report on the state of the 19th century American fishing industry by a civil servant called Lorenzo Sabine. But Sabine was much more than a bureaucratic pen-pusher. He engaged in a number of careers, including some unsuccessful business ventures, and also held public office for a time in the Maine House of Representatives and as Deputy Commissioner of Customs.

As an author, in his research and his publications he showed a passionate desire to reach the truth, being encouraged and applauded by no less a person than the revered historian Jared Sparks, President of Harvard College, now Harvard University.

Writing about what an author considers to be the truth

can be controversial, and Sabine’s best-known work was no exception, landing

him in hot water with ‘patriotic’ Americans. We all know that the American

Revolution War between 1775 and 1783, also known as the War of Independence,

resulted in a humiliating defeat for Britain.

Not everyone knows that British troops were helped by Loyalists in the American colonies who rejected the idea of republicanism and remained staunchly devoted to the Crown, supporting British rule in the colonies. I didn’t know that the terms Whig and Tory, first used in 17th century English politics, were used across the Atlantic to distinguish between the rebels – or patriots, as Americans today would call them – and the Loyalists.

Celebrating an American victory on 14 October 1781: ‘Storming a Redoubt at Yorktown’ by the French artist Eugène Lami (1800–1890). Image credit: Wikipedia

From early childhood, Lorenzo Sabine, in his own words, was ‘revolution-mad.’ But, not until 1821, when he moved to the state of Maine and was close enough to pursue his passion, did he realize how much rich material there was for an historian to study, based on the memories of people who had fought on the two sides.

Prior to his revelations, most Americans believed, in his words, that ‘every “Tory” was as bad as bad could be, every “son of Liberty” as good as possible.’ Sabine discovered, as he put it, that ‘there was more than one side to the Revolution’.

In 1847, sixty or so years after the dramatic events which led to American independence, Lorenzo Sabine published the results of his research in the North American Review, the United States' first literary magazine. His studies, he wrote, had convinced him that ‘all who called themselves Whigs were not necessarily disinterested and virtuous, and the objects of unlimited praise, and the Tories were not to a man selfish and vicious, and deserving of unmeasured and indiscriminate reproach.’

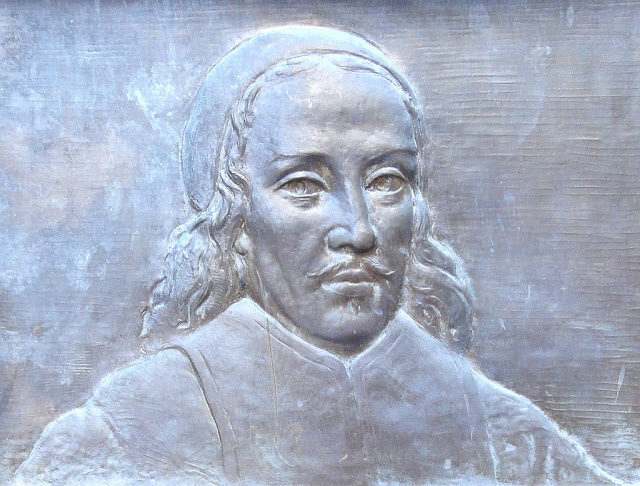

William Franklin FRSE (1730 –1813),

a steadfast Loyalist throughout the American Revolutionary War, was an

American-born attorney, soldier, politician, and colonial administrator. He was

the acknowledged illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin. His father by contrast

was one of the most prominent of the Patriot leaders of the American Revolution

and a Founding Father of the United States. The painting is attributed to the American

artist Mather Brown (1761-1831). Image credit: Wikipedia

Sabine’s findings were controversial, but his ideas appeared in book form. His Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution, with an Historical Essay, was published in two volumes by Little, Brown and Company in Boston.

In his preface he pondered on the question of why so little was known of the Loyalists. ‘The reason is obvious,’ he concluded. ‘Men who, like the Loyalists, separate themselves from their friends and kindred, who are driven from their homes, who surrender the hopes and expectations of life, and who become outlaws, wanderers, and exiles, - such men, leave few memorials behind them. Their papers are scattered and lost, and their very names pass from human recollection.’

For Sabine, Roger Conant similarly resembled one of those forgotten historical figures. His Report on the Principal Fisheries of the American Seas, prepared for the Treasury Department of the United States was published in Washington in 1853.

Judging by the title it appeared to be a somewhat unexciting document; it was destined, as the front page tells us, to be submitted by the Hon. Thomas Corwin, Secretary of the Treasury as ‘a part of his annual report on the nation’s finances at the second session of the thirty-second Congress’. In fact Sabine’s report, along with the tables and statistics that one might expect from such a report, included a lively and most readable history of the American fishing industry from earliest times. It included his own theory that the Plymouth Pilgrims had set sail for the New World on the Mayflower partly to profit from the plentiful fishing grounds of America’s east coast.

Thomas Corwin, incidentally, was known for his sharp wit, being quoted for this aphorism by the Canadian humourist Stephen Leacock: ‘The world has a contempt for the man who amuses it. You must be solemn, solemn as an ass. All the great monuments on earth have been erected over the graves of solemn asses.’

Sabine expressed similar feelings in relation to Roger Conant’s place in history. ‘If men would be remembered by those who come after them, they must win battles, or acquire positions in the State,’ he wrote in his Report on the Principal Fisheries for Thomas Corwin. ‘Roger Conant was but a humble superintendent of a fishery, and of a plantation undertaken among the bare rocks of Gloucester, and is forgotten.’

He went on in his report to tell the story of Conant’s intervention ‘at the point of collision and bloodshed’ in the stand-off between the Cape Ann fishermen and the Plymouth Puritans at Cape Ann, the subject of John Washington’s recent painting seen above.

Myles Standish, incidentally, he describes as ‘the renowned Indian-slayer’ – perhaps a bitter reflection on the fame achieved in battles won by English settlers against Native American tribes thanks to the skills and ruthlessness of this Plymouth Puritans’ military officer. The later 19th century in America would see a number of monuments dedicated to Standish, as well as at least two forts, two towns and a forest named after him. The Duxbury monument shown above, finished in 1898, is the third tallest monument to an individual in the United States.

Roger Conant had achieved nothing like such fame in 1853. ‘His history has not been written; it exists only in fragments,’ reads the Report on the Principal Fisheries. ‘He was a good man. He possessed the true test of merit, for he never clamored, or even asked, for reward.’

Sabine had evidently read the petition of 1671 which Conant had addressed to the magistrates of the General Court at Salem and felt that he did indeed deserve reward. He had, after all, remained steadfast and continued to lead the party of settlers at the colony of Naumkeag – later to be named Salem – when many of them had absconded, either returning home or going further south.

In Conant’s own words, when, ‘in the infancy thereof’,

Naumkeag ‘was in great hazard of being deserted, I was a means, through grace

assisting me, to stop the flight of those few that were heere with me, and that

by my utter deniall to goe away with them, who would have gon either for

England or mostly for Virginia, but thereupon stayed to the hassard of our

lives.’

Sabine went on to mention Conant’s wish to change the name of the town of Beverly, frustrated by the refusal in 1671 of the magistrates of the General Court at Salem. ‘In his old age, he did indeed petition, that as “Budleigh,” in England, was his birthplace, so “Budleigh,” in America might be his burial place; but this poor boon was denied to the Christian hero, who stood by and saved the colony in the hour of extremity.’

John Wingate Thornton in 1870. Image credit: Wikipedia

Lorenzo Sabine’s wish to see Roger Conant’s achievements recognised was partially fulfilled in the year after his fisheries report was published. The lawyer and author John Wingate Thornton’s book The Landing at Cape Anne or The Charter of the first permanent colony on the territory of the Massachusetts Company (1854) has this judgement of Salem’s founder:

‘Conant was moderate in his views, tolerant, mild and conciliatory, quiet and unobtrusive, ingenuous and unambitious, preferring the public good to his private interests; with the passive virtues he combined great moral courage and an indomitable will. His true courage and simplicity of heart and strength of principle eminently qualified him for the conflicts of those days of perils, deprivation, and trial.’

The Conant memorial window in the church at Dudley, Massachusetts. Image credit: Chris Mayen

Sabine did not live to see the first-ever monument in America which honoured Roger Conant. This was the fine memorial window commissioned for the Conant Memorial Church in Dudley, Massachusetts, but sadly destroyed during a storm on 8 June 1946. Roger’s descendant, the 19th century inventor and industrialist Hezekiah Conant, who funded the church, published a souvenir booklet in 1883. This is what he wrote about his ancestor:

‘The memorial window, representing Roger Conant separating the combatants, is appropriate and not objectionable, it seems to me, and I prefer it to any picture of celestial beings. It represents an event in history, and it also shows a characteristic of that eminent person. I do not know that he was strictly a Puritan, yet he was a religious man, and a person who commanded the confidence and respect of the community in which he lived, and his character has no stain. And though he never was canonized by any ecclesiastical authority, yet when he prevented this quarrel he certainly was entitled to the reward promised by Christ himself, who said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

Lorenzo Sabine’s grave. Image

credit: www.findagrave.com

Lorenzo Sabine died in Roxbury,

Massachusetts on 14 April 1877. He was interred in Hillside Cemetery at Eastport

in the state of Maine.

I know that he would be delighted with what we are doing in Roger Conant’s home village of East Budleigh to honour this decent, modest pioneer of American history. Contributions towards the cost of the blue plaque to commemorate him are most welcome. You can read more at

https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/michael-downes-1