Looking for frightfully fun events around Halloween this year? For haunted happenings? It’s a time when visitors from all over the USA flock to ‘The Witch City’, also known as Salem, Massachusetts. If you’re feeling energetic there’s even a Witch City 5k Road Race on 15 October, when you can run through Salem’s supposedly haunted streets. ‘The ghouls, ghosts and goblins will be with you in spirit this year!’ promise the organisers.

Collins Cove, Salem, Massachusetts

One of Salem’s ghosts in particular is said to be that

of a young woman dressed in a cape who can be seen walking along the shores of Collins

Cove on foggy nights. She is said to be looking for her beloved lost husband

who was buried apart from her. Or perhaps she is searching for her own lost

grave, or pining away seeking a return to her home in the English countryside

of 400 years ago.

Indeed she was English,

with deep roots in the county of Lincolnshire, yet with family links that would

bind her to Devonshire, even to this part of East Devon.

To understand her rather poignant connections between the homeland of Ralegh and Conant, the Lincolnshire Wolds and the so-called Witch City you need first to look at this logo which displays the arms of the Clinton barony. You see it everywhere in the Budleigh area, from farm vehicles to industrial estates.

Lord Clinton and me in my amazing costume at the opening of the Raleigh 400 exhibition at Fairlynch Museum, Budleigh Salterton, 28 May 2018. Image credit: Lizzie Mee

The 22nd Baron Clinton, pictured above, with his family seat at Heanton Satchville in North Devon is the largest private landowner in the county, holding 25,000 acres of land managed by Clinton Devon Estates, a land management and property development company.

Away from Devon and the West Country, on the other side of England, is Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire. Next to it you see the arms of the Earls of Lincoln, described in heraldic terms as 'Argent, six crosses crosslets, three, two, and one, sable, on a chief azure two mullets or pierced gules'.

The ‘Darnley Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I of

England. Image credit: Wikipedia

However the following century saw the English monarchy

in trouble. Elizabeth had successfully steered a middle way in religious matters.

On one side were the Puritans who felt that the Church of England, while

Protestant in name, needed further reform to rid it of ‘popish’ trappings. On the other were traditionalists who were still attached to Anglo-Catholic

practices and beliefs.

Portrait of King James I and VI after the artist John de Critz, c. 1605. Image credit: Wikipedia

Elizabeth’s reign came to an end with her death in 1603. For many Puritans the accession

of King James I must have seemed an opportunity to further reform the Church of

England, especially as the new king had been brought up in Scotland where the

Protestant Reformation had been strong, led by theologians like John Knox.

Early in his reign, James was presented with a list of requests contained in the Millenary Petition, said to have been signed by 1,000 Puritan ministers. The document expressed Puritans’ distaste for many Anglican customs and ceremonies, including what they saw as superstitious practices with echoes of Catholicism.

The Hampton Court Conference of 1604, presided over by the king, resulted in the acceptance of some of the Puritans’ demands, but the more radical among them remained dissatisfied.

Adding to the tensions between king and Parliament was the political opposition to the idea of a Spanish marriage for the heir to the throne, James’ son Charles, Prince of Wales. High level negotiations to secure the marriage were conducted over a decade between 1614 and 1623. It never took place, but the plan provoked much anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic feeling.

Radical Puritans, particularly in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, had been persecuted during the reign of Elizabeth, with fines imposed by the government for failure to attend services in their parish church. By 1605 some of them were forming separatist congregations.

Memorial at Immingham, Lincolnshire, to the departure

of congregation members for Holland in 1608. Image credit: Paul Glazzard www.geograph.org.uk

Although Tattershall Castle remains today the most imposing of the Earls of Lincoln’s properties the Clinton family home was actually in the Lincolnshire village of Sempringham. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the English Reformation Edward Clinton, the 1st Earl, used the site of the former priory to build a mansion which is thought to have been almost as large as some of the great Tudor palaces of the day.

Nothing remains of the mansion today, but in the Sempringham Register we find this burial record relating to the 2nd Earl: ‘Henry, layt Earl of Lincoln, departed out of this life at his manor house of Sempringham, this XXIX day of September, anno domini 1615.’

The parish church of St Andrew, Sempringham, where the Rev Samuel Skelton was curate. Image credit: Richard Croft; Wikipedia

It was here that one of the most significant centres of Puritanism took root. The Reverend Samuel Skelton, an ardent Puritan, became curate of Sempringham in 1615. Later he would move to New England, having been recruited by John Endecott, the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who considered him as his spiritual father.

Elizabeth Fiennes de Clinton, Countess of Lincoln, painted by the Master of the Countess of Warwick. Image credit: Wikipedia

The 3rd Earl, Thomas Fiennes Clinton (1571-1619), is described in the History of Parliament as ‘a strong puritan’. His wife, born Elizabeth Knyvet (c.1570-1638) was certainly following Puritan views when in 1622 she wrote an advisory pamphlet entitled The Countess of Lincoln's Nursery, one of the earliest treatises on the advantages of breast-feeding.

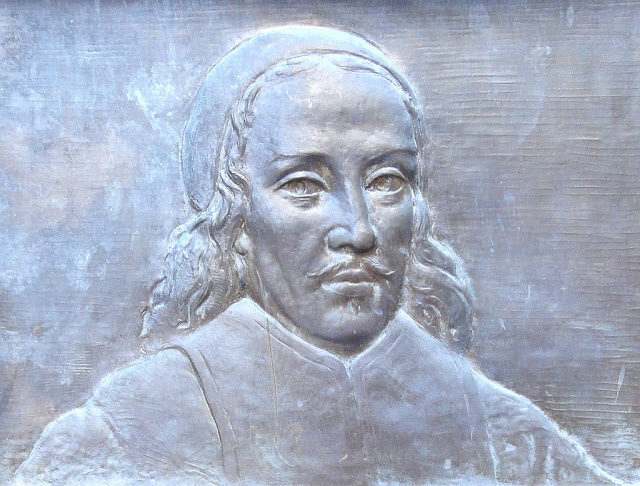

John Dod by Thomas Cross, from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. Image credit: Wikipedia

The previous year had seen the publication of a work by the dissenting clergyman John Dod, developed from a 1598 pamphlet by his co-author Robert Cleaver. In A Godly Form of Household Government (1621), they stated that maternal breast-feeding was both natural and divinely ordained: ‘Amongst the particular duties that a Christian wife ought to perform in her family, this is one, namely, that she nurse her owne children: which to omit, and to put them foorth to nursing, is both against the law of nature and also against the will of God.’

A 1617 edition of John Dod's A plaine and familiar exposition of the tenne commandements.

Ejected in 1607 from his parish at Hanwell,

Oxfordshire, because of his Puritan views, Dod was known as ‘Decalogue Dod’ for

his emphasis on the Ten Commandments.

This sign at the approach to the Massachusetts town of Brewster proclaims 'Brewster welcomes you Twinned with Budleigh Salterton, England'. The second statement may surprise many Budleigh people. Image credit: Christopher Wroten

Some local residents will be familiar with Brewster as

the name of the town on Cape Cod with which Budleigh Salterton is said to be

twinned.

A first-person historical interpreter

portraying Elder William Brewster at Plimoth Plantation. Image credit: Becurry

The Massachusetts town was named in honour of William Brewster, born around 1566, most probably at Scrooby, Nottinghamshire. He was famous as the elder and leader of the Puritan separatist community which had started with the voyage of the Mayflower in 1620. As one of the group who had left Immingham secretly in 1608, he began clandestinely printing books with co-religionist Thomas Brewer in Holland from 1617 to 1619 until their press was shut down by the Dutch authorities.

William Gouge (1575-1653) by the British artist Gustavus

Ellinthorpe Sintzenich 1821-1892. Image credit: Wikipedia

Another Puritan supporter of maternal breast-feeding with a link to the Budleigh area was the preacher and writer William Gouge. His book Domesticall Duties, published in the same year in which the Countess of Lincoln’s work appeared, went through twelve printings over the course of the century, ten after 1626. It celebrates breast-feeding as the highest expression of motherly love: ‘How can a mother better express her love to her young babe than by letting it suck of her owne breasts?’ he wrote. A member of the Westminster Assembly like Roger Conant’s elder brother John, he was also minister for 45 years from 1608 at the church of St Ann Blackfriars, London, where Roger Conant married Sarah Horton in 1618.

Sempringham’s mansion and indeed Tattershall Castle must have been lively homes, with eighteen children born to the Earl and Countess of Lincoln between 1599 and 1615. Religion would have been a popular subject of conversation with the family against the area’s background of so many separatist Puritans who wanted a complete break from the Church of England.

View of Emmanuel College Chapel in 1690 by the

British artist David Loggan (1634-1692). Image credit: Wikipedia

A significant influence on Thomas

and Elizabeth’s eldest son Theophilus, born in 1599, would have

been his attendance at Emmanuel

College, Cambridge.

The so-called ‘famous hot-bed of Puritanism’ had been founded by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Queen Elizabeth I, with the intention of educating Protestant preachers.

Emmanuel College window installed in 1884. It depicts, left, former student John Harvard (1607-1638) the

Puritan clergyman founder of Harvard University; next to him is an image of

Laurence Chaderton (1536-1640), a Puritan divine who was the first Master of Emmanuel

College. Image credit: Dolly442-Wikipedia

It has been shown that of 130 men from English universities who took part in the religious emigrations to America before 1646, no fewer than 100 had studied at Cambridge, of whom 35 had been at Emmanuel.

Portrait of Anthony Tuckney (1599-1670) by the engraver

Robert White (1645-1703) in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Image credit: Wikipedia

When Theophilus Clinton-Fiennes inherited the title as the 4th Earl of Lincoln on his father’s death in 1619, it was only natural for him to appoint as his household chaplain a contemporary of his from his time at Emmanuel, the Lincolnshire-born Puritan divine Anthony Tuckney pictured above.

The Puritan gentry and nobility believed in the importance of religion when marriage was being considered by a family, and Theophilus must have felt that he had found a suitable wife in Bridget Fiennes. Born in 1604 at the family seat of Broughton Castle, near Banbury, Oxfordshire, she was the only daughter of William Fiennes, 8th Baron Saye and Sele and his wife, the former Lady Elizabeth, Baroness Dasset Temple.

William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele (1582-1662) by the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677) From the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Image credit: Wikimedia

Lord Saye, the new earl’s father-in-law, was a staunch Puritan who shared the aims of the Banbury area’s representatives in Parliament, namely promotion of Protestantism and opposition to the Crown’s fiscal policies. His son, James Fiennes who became Member of Parliament for Banbury in 1626, had attended Emmanuel College, Cambridge, like Theophilus.

L-r: Actors

Ralph and Joseph Fiennes and explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes OBE, all members of the Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes

family and descendants of William

Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele. Image credit: Wikipedia

And for those readers interested in such things descendants of the family include the actors Ralph and Joseph Fiennes and the explorer Ranulph Fiennes.

Soon after the marriage of his daughter to Theophilus, Lord Saye found himself as one of the most vociferous leaders of the opposition to the government. He refused to contribute to the benevolence – a sum of money disguised as a gift. The king had requested the contribution in order to aid his son-in-law Frederick, Elector of the German state of the Palatinate. So vigorous was his opposition that Saye was arrested and spent eight months in London’s Fleet Prison from 6 June 1622.

Charles I in Three Positions by the Flemish painter Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599 - 1641). Image credit: Wikipedia

Theophilus similarly found himself at odds with royal authority when in 1626 he opposed James’ successor, King Charles I. The new king tried to raise money without Parliament through a forced loan levied on all taxpayers and imprisoned without trial a number of those who refused to pay it. Among them was Theophilus, Lord Lincoln who was imprisoned in the Tower of London. He was said to be the author of a pamphlet which accused the king of seeking ‘the overthrow of parliament and the freedom that we now enjoy’.

Theophilus also shared his father-in-law's enthusiasm for colonising America. When the Providence Island Company was founded in 1629 to settle that area of the Caribbean, Lord Saye was one of the shareholders. Later, in 1635, Saye would co-found with Robert Greville, the second Baron Brooke of Warwick Castle, the independent colony of Saybrook in Connecticut, named after the pair.

Thomas Dudley had joined the Lincoln household at Sempringham in 1616 as steward to the 3rd Earl. With a military background, like the young Walter Ralegh many years previously, he had fought for the Huguenots in the French Wars of Religion before gaining some legal training and entering the Earl’s service. According to Dudley’s biographer Augustine Jones he also had an important role in securing the engagement of Theophilus Clinton to Lord Saye's daughter Bridget Fiennes.

The accession of Charles I as king in 1625 marked a

new period of persecution for Puritans, particularly with the growing influence

of the future Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud and his drive for

uniformity in the Church of England.

Queen Henrietta Maria by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, in the collection of San Diego Museum of Art. Image credit: Wikipedia

Lincolnshire’s Puritans would have been disturbed by the news that the new king’s wife, Henrietta Maria, was a Catholic and would be free to practise her religion. There is evidence that Thomas Dudley played an important role in the plan to colonise America for religious motives, discussing the idea with members of the Sempringham household.

The memorial plaque for John Cotton, near the John Adams Courthouse, Boston, Massachusetts. Image credit: Wikipedia

He had been inspired by the preaching of the Puritan minister John Cotton, vicar of St Botolph’s in Boston, and according to a letter that he later wrote to the Countess of Lincoln, it was in about 1627 that he and friends in Lincolnshire ‘fell into discourse about New England and the planting of the Gospel there’.

The idea was evidently taken seriously, for by the following year, after dispatching ‘letters and messages to some in London and the West Country’ and ‘with often negotiations so ripened’, royal permission was obtained. ‘We procured a patent from His Majesty for our planting between Massachusetts Bay and Charles River on the south, and the River Merrimac on the north, and three miles on either side of those rivers and bay,’ explained Dudley.

The venture for which this patent was obtained was first styled the New England Company, later to be renamed the Massachusetts Bay Company. Some of the investors in the new enterprise had previously invested in Pastor John White’s Dorchester Company which had established a short-lived settlement at Cape Ann with Roger Conant as its governor.

Portrait of the first governor of the

Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Endecott, by an unknown artist. Image credit: Wikipedia

A preliminary expedition of about 50 ‘planters and servants’ was led by John Endecott, who would become the longest-serving governor of what became known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It set out for the New World on 20 June 1628 aboard the Abigail, landing at Naumkeag – later to be called Salem.

Sempringham’s

curate Samuel Skelton, who may have acted as chaplain to the Earl of Lincoln,

has been described by some historians as Endecott’s spiritual father.

Together with his family he arrived at Naumkeag on 23 June 1629. He would become the first pastor of the First Church of Salem, seen as the original Puritan church in North America.

Portrait

of John Winthrop by an unknown artist. Image credit: Wikipedia

At around this time the Puritan lawyer John Winthrop became involved with the Massachusetts Bay Company. He may have learnt of its plans through the Rev John Cotton. The two of them had both been students at Trinity College Cambridge. Cotton would go on to study at Emmanuel College before becoming vicar of St Botolph’s, Boston, in 1612.

In March 1629, King Charles dissolved Parliament, having resolved to rule Britain alone. Puritans like Winthrop were increasingly convinced that religious freedom could be achieved only by emigrating. On 20 October he was elected as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company in succession to the London merchant Matthew Cradock,

a

Puritan shipowner with international business interests and a fleet of at least

18 vessels.

An image of the replica of Arbella built for the 300th anniversary of Salem in 1930 in conjunction with the city’s Pioneer Village. Image credit: Wikipedia

On Thursday 8 April 1630 the first of the 11 ships that became known as the Winthrop Fleet set sail from Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight, including its flagship the Arbella. The Fleet carried a total of about 700 passengers, some of them on vessels that set out in the following month.

Many of the passengers were economic migrants, resulting from the recession from which much of Eastern England and the West Country had been suffering since the early 1620s.

From the Earl of Lincoln’s Sempringham household and also aboard the flagship were his steward Thomas Dudley accompanied by his wife Dorothy and their children Thomas, Samuel, Mercy, Sarah, Patience and Anne, the latter with her husband Simon Bradstreet who had succeeded Dudley as the Earl’s steward.

Theophilus himself stayed in England, but his brother Charles Fiennes-Clinton and his sister Arbella sailed on the flagship which had been renamed in her honour, having been previously named the Eagle.

Lady Arbella Johnson, as she was known, was accompanied by her husband the Rev Isaac Johnson, a Puritan clergyman who was the largest shareholder of the Massachusetts Bay Company. The couple would reach the New World when the flagship arrived in Salem Harbour on 12 June 1630.

But Lady Arbella had been taken

ill on the voyage and died at Salem in August of that year ‘thus remaining ever

young and beautiful’ as one of America’s legendary figures, as my

fellow-blogger and Salem historian Donna Seger puts it.

The death a month later of her

husband Isaac – ‘young, articulate, wealthy, committed to the cause, and

apparently very much in love with the fair Arbella’ – could only add to the

pathos. ‘Certainly one of the most romanticized women in Salem’s history’ is

how the lady is described if you click here

Or, if you believe the Halloween stuff, possibly Salem's oldest English ghost.

But I like to think of Lady Arbella as one of the links between Salem and Devon. A second link was forged when yet another Puritan marriage was made for a Clinton family member. That took place in 1643 when Lady Arbella’s niece, the younger daughter of Theophilus, Lady Arabella Fiennes-Clinton married the descendant of yet another English clan which, like the Earls of Lincoln, owed its immense wealth to the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the Reformation.

Arabella’s husband was Robert Rolle, the great-great-grandson of George Rolle, a Dorset-born London lawyer who was elected Member of Parliament for Barnstaple in North Devon during the 1540s and purchased much ex-monastic property, becoming the founder of one the county’s great landowning dynasties.

The Rolle Arms, one of East Budleigh’s two pubs. In Budleigh Salterton, one of the town’s best hotels was The Rolle Arms on the High Street, since demolished and converted to flats as The Rolle

A biographer of Robert Rolle has written that the whole Rolle clan was seen as deeply and traditionally Puritan, having a hatred of practices such as usury, gaming at cards and dice.

Naturally enough, such influential landowners with Puritan leanings would back Parliament rather than the King during the English Civil Wars. Dissenting from the Establishment, they would play a key role when the country rejected Stuart autocracy in favour of rule by the people in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. But dissent still had some way to go!

No comments:

Post a Comment