Roger Conant on Cape Ann

Part II: The Rescue Party

By Mary Ellen Lepionka, January 2020

The Dorchester Company was officially dissolved in the fall of 1625 as unprofitable and unsustainable. Two ships set sail from Weymouth with relief supplies and instructions to bring home to England any settlers who wanted out. Most of the Zouch Phoenix arrivals had stayed through the winter of 1624-1625 along with the few fishermen remaining from the first season. The Company ultimately would occupy Fishermen’s Field from the winter of 1623-1624 to the fall of 1626, when the site was abandoned. This amounted to two and a half years comprising three winters, three fishing seasons, and two growing seasons. White blamed the venture’s failure as much on poor leadership and unproductive labor as on poor fishing and planting and the vicissitudes of international markets. He also observed that fishing and planting require entirely different settings and conditions, that fishermen do not necessarily make good builders and planters and vice versa, that laying the foundation for a colony involves sunk costs that cannot be recovered, and that colonies cannot be expected to become profitable right away:

"Two things withall may be intimated by the way, the first, that the very proiect it selfe of planting by the helpe of a fishing Voyage, can never answer the successe that it seemes to promise (which experienced Fisher-men easily have foreseene before hand, and by that meanes haue preuented divers ensuing errors) whereof amongst divers other reasons these may serue for two. First that no sure fishing place in the Land is fit for planting, nor any good place for planting found fit for fishing, at least neere the Shoare. And secondly, rarely any Fisher-men will worke at Land, neither are Husband-men fit for Fisher-men but with long vse & experience. The second thing to be obserued is, that nothing new fell out in the managing of this stocke seeing experience hath taught vs that as in building houses the first stones of the foundation are buried vnder ground and are not seene, so in planting Colonies, the first stockes employed that way are consumed, although they serue for a foundation to the worke."

White nevertheless was desperate to protect the Company’s property and interests on Cape Ann and to provide leadership, religious stewardship, and provisions for the settlers who had chosen to remain. John Conant, a Dorchester Company investor and Pastor of Lymington, alerted White to the fact that his brother Roger Conant had emigrated to New Plymouth in 1623 and might make a good manager for the Company’s affairs at Cape Ann. The Company wrote to Roger Conant inviting him to come up from Plymouth to manage the property until it could be disposed of through the bankruptcy proceedings and to lead those who stayed, along with any new settlers who showed up. Conant was at Nantasket (present-day Hull, Massachusetts) at the time with some ex-Plymouth fishermen, helping to operate a satellite fishing station and trading post for the lucrative fur trade with the Wampanoag.

Roger Conant, a London salter (saltmaker and trader in salt), and his brother Christopher, a London grocer, had settled in Plymouth with their families in 1623. They apparently disliked the religious intolerance of the Pilgrims, however, and the Separatist sentiments they found there, including the so-called Brownists, whose efforts led ultimately to the establishment of the Congregational Church in New England. Separatism vs. ecclesiastical reform—breaking away from the Church of England versus changing the way it was conducted—and Royalists vs. Parliamentarians—having a monarchy vs. a representational democracy--were religious and political issues in the coming English Civil War of 1642-1651, which was dividing English settlers in the colonies as well. The Conant families left for Nantasket in 1624, following the anti-Separatist and Royalist Puritan preacher John Lyford and the free-thinking trader John Oldham, both of whom had made themselves unwelcome in William Bradford’s Plymouth Plantation.

Conant accepted the Dorchester Company’s offer and joined the Zouch Phoenix settlers at Fishermen’s Field in the summer of 1625. He brought his family with him (a wife and two or three children born to them by that time). He also brought Nantasket fishermen Richard Norman and his son Richard Norman Jr. (Norman’s Woe is named for a Norman family loss in a shipwreck on that rock off the Gloucester Massachusetts coast), Thomas Gray, John Gray, Walter Knight (who had likely purchased land at Hull from the Neponset sachem Chickatawbut), Knight’s wife and five children, the Rev. John Lyford, and the trader John Oldham. Oldham subsequently declined an offer of a monopoly on the Cape Ann Indian trade and did not stay with Conant’s party.

Fishermen’s Field at Stage Fort Park, Gloucester, MA

At Cape Ann, Conant found a settlement barely capable of eking its way through the winter of 1625-1626. He soon declared conditions too harsh for a plantation, the soil too poor and rocky, and the fishing grounds too inconveniently far away. He also found that though the men had built a pier and flake yard and had erected a meetinghouse, operations for receiving, salting, and barreling fish had not been developed, and the plantation was inadequate. The plantation harvest (they were trying to grow English barley from imported seed sown in glacial till) was too meagre to feed them. The people were quarrelsome, living in the Pawtuckets’ wigwams, relying on the Indians’ reserves of corn to survive, and falling ill. Conant wrote to White of his resolve to abandon the site. In the fall of 1626 he and a Pawtucket guide led the entire party overland southwest along the coast for 12 miles, driving their cattle before them, via the Squam Trail, to the Pawtucket village of Naumkeag (Nahumkeak), located on the Bass River where it drains Wenham Lake.

The new “Cape Ann Side” settlement that Conant and company founded near Naumkeag was in present-day North Beverly, Massachusetts—not Salem is commonly thought. The confusion stems from the fact that they called their settlement in Beverly “Salem Village”, which at that time also included parts of present-day Manchester-by-the Sea, Beverly, Peabody, Danvers, and Middleton. (In 1628 John Endicott, representing John White’s new New England Company, moved the colony’s seat across the river to present-day Salem.) The first fishing station was on Beverly Harbor below Fish Flake Hill, from the waterfront (Water Street) up to Stone Street and from Bartlett Street to Rantoul Street in present-day Beverly. The English survived their first winters through the hospitality of the Pawtucket people, with whom—by their own accounts—they planted, hunted, and fished side by side, peacefully, for the next 40 years.

Fish Flake Hill Today, Beverly, MA

Accounts differ as to the number of people with Conant on the Squam Trail to Naumkeag. One source cites “20 or 30 Dorchester Company people”, while another notes that only 2 or 3 Dorchester Company men remained. However, the 2 or 3 men must refer to the 2 or 3 “men of substance” (John Balch, John Woodbury, and Peter Palfrey) whom Rev. John White chose to co-govern with Conant at Naumkeag. Learning that the move was a fait accompli, White implored Conant to remain at Naumkeag to maintain the integrity of the Cape Ann effort and to induce the men of substance and any others to stay at the new settlement. According to Hubbard’s account of his interview with Roger Conant:

"…Mr. White, (under God, one of the chief founders of the Massachusetts Colony in New England,) being grieved in his spirit that so good a work should be suffered to fall to the ground by the adventurers thus abruptly breaking off, did write to Mr. Conant not so to desert his business; faithfully promising, that if himself with three others, (whom he knew to be honest and prudent men,) viz., John Woodbury, John Balch and Peter Palfreys, employed by the adventurers, would stay at Naumkeag, and give timely notice thereof, he would provide a patent for them, and likewise send them whatever they should write for, either men or provisions, or goods wherewith to trade with the Indians. Answer was returned that they would all stay on those terms, intreating that they might be encouraged accordingly."

The plaque on Conant’s famous statue in present-day Salem attests to his difficulty in persuading people to stay. The plaque quotes from the following statement in Conant’s report to the Mass. Bay Colony General Court:

"…[When] in the infancy thereof, [the colony] was in great hassard of being deserted, I was a means through grace assisting me, to stop the flight of those few that there then were heere with me, and that by my utter deniall to goe away with them, who would have gone either for England or mostly for Virginia, but hereupon stayed to the hassard of our lives."

Roger Conant Plaque, Salem, MA

Meanwhile, Rev. John White created the New England Company out of the ashes of the Dorchester Company and sent relief supplies to Cape Ann. On March 19, 1627, he had the Dorchester Company’s property transferred to the New England Company for a Plantation on Massachusetts Bay. This was an unincorporated joint stock company with 90 West Country investors, including some of the original Dorchester Company investors, each contributing £50. Richard Saltonstall was the chief shareholder. The very next day, supplies were loaded on two ships at Weymouth under a license to Simon Whetcombe and associates of the new Company. White, himself lacking the funds to invest in the new company, nevertheless fulfilled his promise to resupply the settlers. The relief ships found no one at Cape Ann but managed to locate them at Naumkeag and delivered provisions of cattle, fodder, beef, cheese, butter, soap, oil, beer, and clothing.

Settlers returning to England in 1625 had leaked word about the Dorchester Company bankruptcy and imminent abandonment of Cape Ann, prompting some West Country investors to attempt to claim the abandoned assets, especially the barrels of salt, as a means of recovering their money. They hired a Capt. John Hewes, a Welshman, to sail up from Plymouth on their behalf to seize whatever was there. Thus begins a famous confrontation on Fishermen’s Field in which Roger Conant is credited with averting bloodshed.

When Governor Bradford learned—from Capt. Peirce in the Anne, who was fishing in Gloucester waters at the time—that Hewes was attempting to take over Dorchester Company assets at Cape Ann, he sent Miles Standish with some marines to protect the interests of Plymouth Plantation. Plymouth had a prior claim on Cape Ann. In 1623, the same year that John White received a patent for Cape Ann, Edward Winslow and Robert Cushman of Plymouth purchased a patent for Cape Ann from Lord Sheffield:

"Wynesseth that the said Lord Sheffield…Hath Gyven…for the said Robert and Edward and their associates…a certaine Tracte of Ground in New England in a knowne place there commonly called Cape Anne…Together with the free use of the Bay of Cape Anne…and free liberty to ffish, fowle, etc. and to trade in the lands thereabout, and in all other places in New England aforesaid whereof the said Lord Sheffield is or hath byn possessed…Together also with ffive hundred Acres of free Land adioyning to the said Bay…for the building of a Towne, Scholes, Churches, Hospitals, etc. also Thirty Acres of Land and besides…to be allotted…for every particular person that shall come and dwell at the aforesaid Cape Anne within Seaven yeares next after the Date hereof."

Unaccountably, Sheffield had promptly sold his charter to Plymouth. The sale was unauthorized and therefore unenforceable. Bradford referred to it as a “useless patent” and complained that he had been “dispossessed of Cape Ann by West Country adventurers”. In 1624 the Plymouth Company nevertheless tested the waters by sending a fishing expedition and salter to Cape Ann to set up a saltworks and erect a stage at Gloucester Harbor. They found the Dorchester Company already there with a patent of its own and the rudiments of a plantation on Fishermen’s Field.

In its rush to get Puritan colonies going in New England, in competition with Pilgrim colonies as well as with the more prosperous Virginia Colony, the Council for New England had awarded charters for Cape Ann to both Rev. John White and Lord Sheffield, a real grounds for conflicting claims to Cape Ann. In addition, there was Ferdinando Gorges’ and John Mason’s earlier King’s Grant (from King James I), which had included all of eastern North America north of the Virginia Colony and predated even the founding of Plymouth.

So the historical marker commemorating that confrontation is not accurate. Roger Conant’s intervention may have averted bloodshed—Miles Standish did threaten Hewes and his men—but there were really three factions, not two, and they were not contending for a fishing stage. They were contending for all the Dorchester Company’s assets there, and Plymouth in addition was attempting to enforce its claim to Cape Ann.

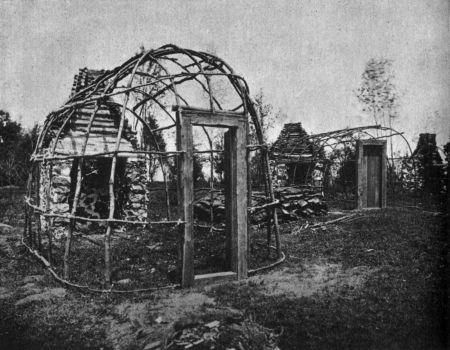

"Modified wigwams with chimneys instead of smoke hole"

In any case, if the Dorchester Company was abandoning Cape Ann, Bradford wanted to claim it for Plymouth and build a permanent fishing station there. According to accounts of the 1625 confrontation, Hewes and his men barricaded themselves behind barrels of salt in the flake yard and Standish threatened to open fire on them, when Roger Conant and company “rushed from their huts” (modified wigwams with chimneys instead of smoke hole) to explain that by English law everything in Fishermen’s Field was still Dorchester Company property pending the outcome of bankruptcy proceedings. With that, all the parties dispersed. The West Country men under Capt. Hewes left for Plymouth’s trading post at Cushnoc on the Kennebec River near present-day Augusta, Maine. They had managed to steal some barrels of salt from Fishermen’s Field, which they sold en route at a trading post at Piscataqua, New Hampshire. Ten years later, John White sued the West Country merchants who had employed them to repossess that salt. Meanwhile, Bradfort recalled Capt. Peirce and Miles Standish to Plymouth, and Roger Conant and his rag tag retinue left Cape Ann for Naumkeag.

(To be continued. Part III is on Roger Conant in Naumkeag.)

Sources:

Adams, Herbert B. The Fisher Plantation of Cape Anne, 1882. Part I of The Village Communities of Cape Ann and Salem, Historical Collections of the Essex Institute: 19. (Salem, MA).

Babson, John. 1860. History of the Town of Gloucester, pp. 16-18.

Bradford, William. Bradford’s complaint of having been dispossessed of Cape Ann by adventurers is in several letters and his commonplace book. His account of the confrontation in Fisherman’s Field is in his entries for 1626 in his History of Plimoth Plantation. For Plymouth on Cape Ann prior to Dorchester Company arrival see Bradford, Records of the Great Council of Plymouth (February 18, 1622-1623).

Bradford, William and Edward Winslow, Mourt’s Relation, or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth (1622).

Bremer, Francis Bremer. 1996. The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards; also Bremer and Webster, eds. 2006. Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia.

Conant, Frederick Conant. 1877. History and Genealogy of the Conant Family in England and America (http://www.archive.org/details/historygenealogy00cona).

Gannon, Fred A. n. d. Roger Conant and the Fishing Station of 1626. In Some Starts of Industry and Commerce in Old Salem. Salem, MA: J. N Simard.

Gardner, Frank. 1907. Thomas Gardner, planter (Cape Ann, 1623-1626; Salem, 1626-1674).

Gorges, Ferdinando. Sir Ferdinando Gorges and His Province of Maine: A Briefe Narration... (1658); America Painted to the Life…. (1659); and Letter relating to Maine, Essex Institute Historical Collections 7: 271 (1661).

Hubbard, William. 1815. A General history of New England: from the discovery to 1680. Volume 5 of Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Boston, MA: Hilliard & Metcalf.

Knight family of Salem, Early records of. Essex Institute Historical Collections 2: 256.

Levett, Christopher. 1628. A Voyage into New England Begun in 1623 and Ended in 1624, Performed by Christopher Levett, his Majesties Woodward of Somersetshire, and one of the Councell of New-England. London: William Jones, for the Council of New England.

Maverick, Samuel. 1660 (Reprinted 1885). A Briefe Description of New England and the Severall Townes Therein, Together with the Present Government Thereof. In New England Historical and Genealogical Register 39: 33-47.

Morton, Thomas (1545-1676). 1637; 1883. Charles Francis Adams, ed. The New English Canaan. Boston: The Prince Society (John Adams Library).

Naumkeag: Good relations among Pawtucket and colonists on Cape Ann and at Naumkeag is attested by Edward Johnson in Wonder-Working Providence of Sions Saviour in New England (1654) and Good News from New England (1658) and by William Wood in New England’s Prospect: A True, Lively, and Experimental Description of That Part of America, commonly called New England (1634): http://www.comity.org/Wood_NE_Prospect.htm.

Norman family of Salem, Biographical sketch and Early records of. Essex Institute Historical Collections 1: 191, 1: 192, 2: 299, 3: 190, 9: 113, 17: 84.

Phillips, Stephen Willard. October 1955. Evolution of Cape Ann Roads and Transportation 1623-1955. In Transportation. Salem, MA: Essex Institute Publications.

Phippen, George D. Biographical sketch of Roger Conant. Essex Institute Historical Collections: 1: 145.

Records of the Great Council of Plymouth, February 18, 1622-1623 (Boston: Commonwealth Museum) and Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England, Vol. I Deeds & Etc. 1620 to 1651, in the Book of Indian Records for Their Lands (Massachusetts Historical Commission Archives, 1861).

Russell, Michael. 2007. Members of the Dorchester Company 1624-1626. In Pilgrims of Fordington & Dorchester Dorset England: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~fordingtondorset/Files/FordingtonDorchesterCo2.html; and Dorchester Company Ships: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~fordingtondorset/Files/RichardBushrod1576.html.

Thornton, John Wingate. 1854. The Landing at Cape Ann: or, The charter of the first permanent colony on the territory of the Massachusetts Company. New York: Gould and Lincoln; August 29, 1862. Colonial Schemes of Popham and Gorges. Speech given at the Fort Popham Celebration, August 29, 1862. Maine Historical Society. Boston: Edward I. Balch (1863).

Webber, Carl and Winfield S. Nevins. 1877. Old Naumkeag: An Historical Sketch of the City of Salem, and the Towns of Marblehead, Peabody, Danvers, Wenham, Manchester, Topsfield, and Middleton. Salem, MA: A. A. Smith.

White, Rev. John. October 12, 1634. The Adventure for 1623-1628 in New England. Proceedings of the Court of Requests of Charles I, London.

White, Rev. John, 1630, The Planter’s Plea (London: William Jones); John White’s Planter’s Plea, 1630, printed in facsimile with an introduction by Marshall H. Saville, The Sandy Bay Historical Society Publications Volume I (Rockport, MA, 1930), pp. 70-77; 79-84.

Wilkie, Richard W. and Jack Tager. 1991. Map of Native Settlements and Trails c. 1600-1650, p.12, Historical Atlas of Massachusetts: http://www.geo.umass.edu/faculty/wilkie/Wilkie/maps.html

Winslow, Edward. 1624. Good Newes from New England: A true relation of things very remarkable at the Plantation of Plimoth in New England (1996 reprint, Applewood Books).

Winthrop, John. 1649 (Reprinted 1908). History of New England 1630-1649. James K. Hosmer, ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. (Also 1853, James Savage, ed., The University of Michigan).

Winthrop Society, the. The Residents of Salem, First Town of the Massachusetts Bay Commonwealth:

From Original Records up to the Year 1651: http://www.winthropsociety.com/doc_salem.php.

Woodbury, Humphrey. Deposition on his father John Woodbury’s arrival in Salem Village in 1624: http://dougsinclairsarchives.com/woodbury/johnwoodbury1.htm#vitals.

Young, Alexander. 1846, Chronicles of the First Planters of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1623-1636, Volumes 41 and 49 (Also Volume 1, p. 12). Boston, MA: C. C. Little and J. Brown.

©

Continued at https://conant400.blogspot.com/2020/02/roger-conant-on-cape-ann-part-iii.html

No comments:

Post a Comment